I love the prologue. It’s famous because Atxaga compares euskara to a hedgehog. What a striking image! Both the language and the animal are strange, small, and unforgettable. As for the title, which to English speakers is a mouthful, Atxaga explains, “And Obaba is just Obaba: a place, a setting: ko means of; a is a determiner; k the plural. The literal translation” The people or things of Obaba; a less literal translation: Stories from Obaba.” And finally, the text declares that this text was originally written in Basque, which if you’re reading this blog is assumed, but for those who are simply paging through the book at a store that might be something intriguing.

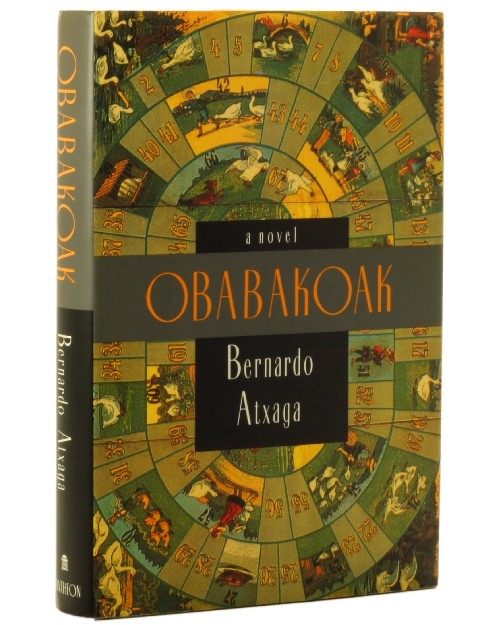

Do we read this as a collection of short stories? A story cycle? Or a novel? The book sleeve calls it a novel, but I when I read what Atxaga said I think a collection of stories. I know publishers hate short story collections because they don’t sell. Where is the center? It’s the town. Obaba functions like Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Outside of how these writers use language, I adore their movement away from realism towards fabulism.

Esteban Werfell

Esteban and his father live in a home with walls covered with books, twelve thousand volumes, that separate him from the outside world (pg. 3). The story begins with him scribbling in his twelfth journal, and we the reader are allowed to watch him write and to read his text directly. There is a meta quality to this opening—reading about a writer writing and reading his own writing and deciding how to write. This self-reflexivity is very post-modern but the content and setting feels traditional—this isn’t John Barth or Philip K. Dick. It reminds me of Alice Munro—set in a simple, small town but the language is very much alive, but the pace is slow and descriptive.

Esteban writes in first person while Atxaga tells his story in 3rd person. This helps with clarity. Even if the text wasn’t indented and the font down-sized, we the reader could clearly tell which author was writing by point of view alone. But pace…nothing really happens. On page eleven we start to find out about the Werfell family, how his father is a mining engineer from Hamburg, Germany and that they moved to Obaba and that the mine closes down and that they are left with worthless stocks (11-12). This fate makes returning to Germany impossible.

What is this story about? The plot is almost nothing. There are so few characters, none of which act as an antagonist. So we are left with Esteban remembering and writing. At least that is until we reach page nineteen when suddenly we are introduced to Maria Vockel who asks, “Do you know what love is, Esteben” (19)? Then she gives Esteban an address in Hamburg. And just then Andrés comes into the story and says that Esteban fainted. This is a perfect example of how an author can suddenly jump start a story by adding characters and plot which increase the pace. It’s at this moment that the story really came to life.

“People in Obaba had no difficulty in accepting even the strangest events. My father used to make fun of them” (22). Here the reader is being keyed into how to interpret the people of this town where the stories are taking place. This is an important task a reader must do at the beginning of every book. Reading is a de-coding process. Shortly after that passage the reader is given, “This was real life, not a novel” (23). No it’s a novel—and we know it. But all of this is making us aware of how these stories are being told.

Esteban tells his father about fainting and the two write a letter to Maria, which they do together because Esteban doesn’t speak German. Sure enough the mystical dream comes to fruition when a letter shows up with Maria Vockel’s name on it. As a result of this letter a rift forms between Esteban and Andres, one that keeps Esteban at home studying German.

Eventually Esteban goes to university and eventually marries a colleague at work. One day he goes to Hamburg and visits Maria Vockel’s house. There he finds an old man, his father’s friend, who penned the letters. “The game lasted until I saw that you were safe,” Esteban’s father wrote in a letter that the old man gave Esteban. What a masterful example of game theory and manipulation.

Question: What do you think about Atxaga’s pace in the beginning of this story? Why start the novel about a small Basque town with Germans? What is the picture he paints of the people of Obaba?