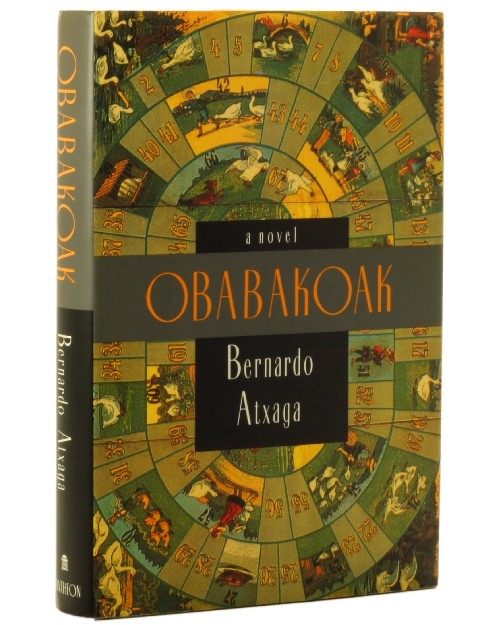

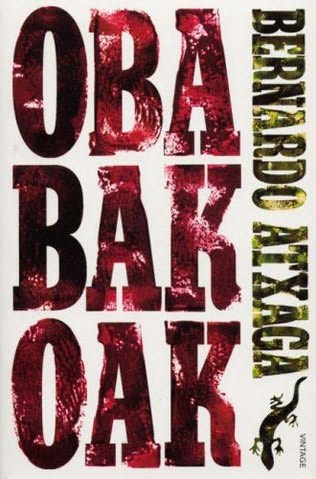

I love the prologue. It’s famous because Atxaga compares euskara to a hedgehog. What a striking image! Both the language and the animal are strange, small, and unforgettable. As for the title, which to English speakers is a mouthful, Atxaga explains, “And Obaba is just Obaba: a place, a setting: ko means of; a is a determiner; k the plural. The literal translation” The people or things of Obaba; a less literal translation: Stories from Obaba.” And finally, the text declares that this text was originally written in Basque, which if you’re reading this blog is assumed, but for those who are simply paging through the book at a store that might be something intriguing.

Do we read this as a collection of short stories? A story cycle? Or a novel? The book sleeve calls it a novel, but I when I read what Atxaga said I think a collection of stories. I know publishers hate short story collections because they don’t sell. Where is the center? It’s the town. Obaba functions like Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Outside of how these writers use language, I adore their movement away from realism towards fabulism.

Esteban Werfell

Esteban and his father live in a home with walls covered with books, twelve thousand volumes, that separate him from the outside world (pg. 3). The story begins with him scribbling in his twelfth journal, and we the reader are allowed to watch him write and to read his text directly. There is a meta quality to this opening—reading about a writer writing and reading his own writing and deciding how to write. This self-reflexivity is very post-modern but the content and setting feels traditional—this isn’t John Barth or Philip K. Dick. It reminds me of Alice Munro—set in a simple, small town but the language is very much alive, but the pace is slow and descriptive.

Esteban writes in first person while Atxaga tells his story in 3rd person. This helps with clarity. Even if the text wasn’t indented and the font down-sized, we the reader could clearly tell which author was writing by point of view alone. But pace…nothing really happens. On page eleven we start to find out about the Werfell family, how his father is a mining engineer from Hamburg, Germany and that they moved to Obaba and that the mine closes down and that they are left with worthless stocks (11-12). This fate makes returning to Germany impossible.

What is this story about? The plot is almost nothing. There are so few characters, none of which act as an antagonist. So we are left with Esteban remembering and writing. At least that is until we reach page nineteen when suddenly we are introduced to Maria Vockel who asks, “Do you know what love is, Esteben” (19)? Then she gives Esteban an address in Hamburg. And just then Andrés comes into the story and says that Esteban fainted. This is a perfect example of how an author can suddenly jump start a story by adding characters and plot which increase the pace. It’s at this moment that the story really came to life.

“People in Obaba had no difficulty in accepting even the strangest events. My father used to make fun of them” (22). Here the reader is being keyed into how to interpret the people of this town where the stories are taking place. This is an important task a reader must do at the beginning of every book. Reading is a de-coding process. Shortly after that passage the reader is given, “This was real life, not a novel” (23). No it’s a novel—and we know it. But all of this is making us aware of how these stories are being told.

Esteban tells his father about fainting and the two write a letter to Maria, which they do together because Esteban doesn’t speak German. Sure enough the mystical dream comes to fruition when a letter shows up with Maria Vockel’s name on it. As a result of this letter a rift forms between Esteban and Andres, one that keeps Esteban at home studying German.

Eventually Esteban goes to university and eventually marries a colleague at work. One day he goes to Hamburg and visits Maria Vockel’s house. There he finds an old man, his father’s friend, who penned the letters. “The game lasted until I saw that you were safe,” Esteban’s father wrote in a letter that the old man gave Esteban. What a masterful example of game theory and manipulation.

Question: What do you think about Atxaga’s pace in the beginning of this story? Why start the novel about a small Basque town with Germans? What is the picture he paints of the people of Obaba?

Starting in early August, I will be posting some thoughts on Bernardo Atxaga’s Obabakoak. It is considered to be his best book and I can’t wait to dig into it. So go out and buy a copy (or go to your library or steal your best friend’s copy–just get your hands on the book).

Here is a series of photos from our trip to Idaho City. It’s an old mining town that has become somewhat of a tourist destination. I loved what I saw. The colors and tones produced by the wood, brick, and rusted metals are only found in the American West.

The high-desert of Idaho and sky should be computer wallpaper. So pretty.

I love what happens to wood over time–orange, grey, blue, black.

Oxidation creates amazing colors.

“The Canisters Three”

“Black Angus”

Reminds me of San Francisco

Bricks

One bad boy

Agua, Ura, H2O, Water

The wheels on the bus go….

Just Look at that green

This is a shower bucket, but I found its face.

I grew up playing hockey.

Dusk.

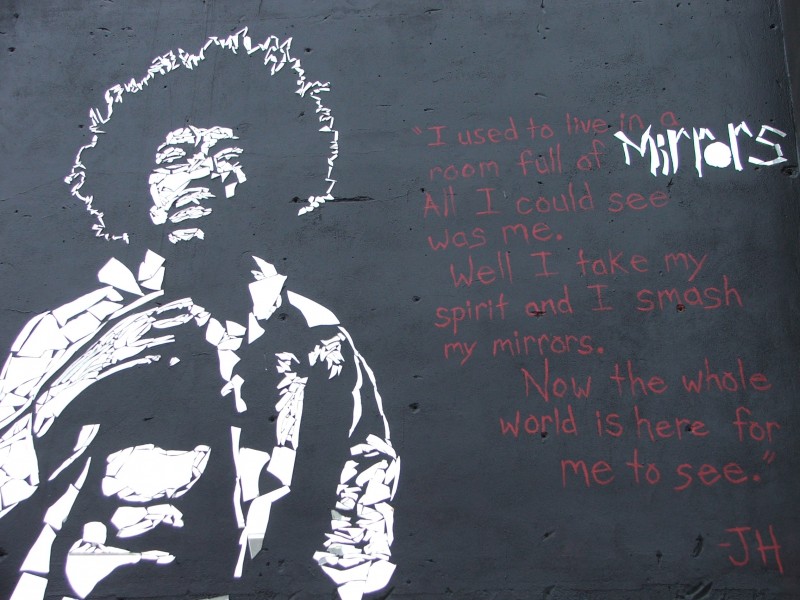

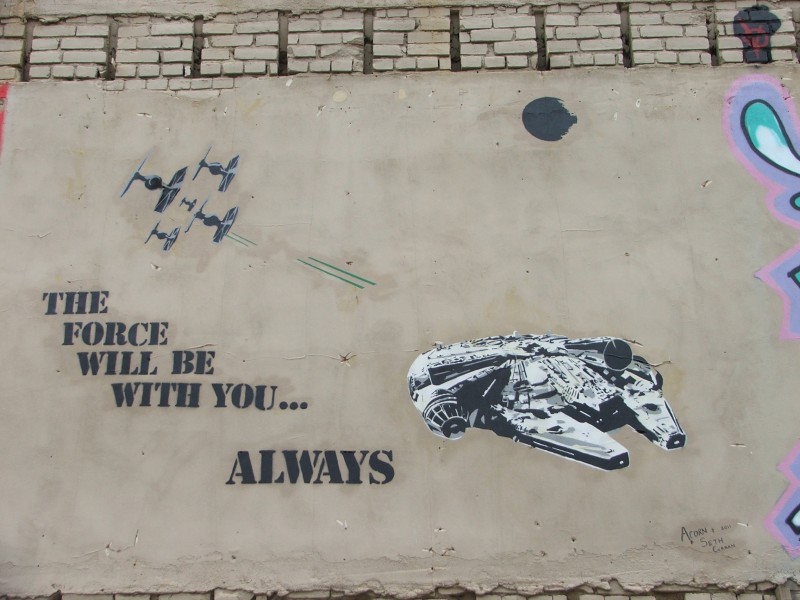

I am in Boise for the Barnetegia and had some time this morning to bum around with my camera. Here are some sweet scratches I saw in a back alley. Who knew?

Let’s approach this story by studying how language is used to create setting, in this case the setting is Bilbao. How do authors represent the world they live in? How do authors use the protagonist’s eyes to see a fictional world? Does that fictional world accurately mime the real world? How do Basque writers represent the rural country, cities, and neighborhoods? Uribarri is a neighborhood in Bilbao and the narrator is a young teenager.

“A Kiss in the Dark” is written in the first person and is a retrospective narration which adds a third aspect: memory. So when thinking about this story we must consider all three layers: the fictional world, the protagonist in his youth, and the retrospective narrator as an adult. These things aren’t mutually exclusive, which makes analysis difficult but is often simply understood by the reader.

The story is on some level recognizable and simple. It reminds me of Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown”, Grimms’ “Hansel and Gretel”, and Borges’ “Labyrinth.” The protagonist makes an across-town journey going from Uribarri to Indautxu through a number of streets that seem foreign.

Something I barely thought about when I read this story for the first time was where these neighborhoods are in Bilbao. There is Calle Uribarri which is just east of the river and because of the mention of crossing the Town Hall Bridge (60) I will imagine the journey being from Calle Uribarri to Indautxu, a journey of 2.3 kilometers that will take 30 minutes to walk. Certainly this won’t be a challenge to most adults but it could be to our young protagonist, who has only gone into the city to visit the cinema or arcade, this errand will take the young man into “the city [that] seemed quite labyrinthine.”

Page sixty shows the reader Bilbao. I don’t have much of a desire to interpret these passages but simply to bring them to your attention: “So this was the perfect occasion to indulge in a thorough exploration of the place: the cinemas, the arcades, the shops where you could exchange comics, all the plush bars; I even spotted a dubious-looking ‘club’ with a red front door [….] I also saw old warehouses, dusty, broken blinds, dark bars and noisy garages.” In this section the protagonist journeys from the commercial neighborhood into more of an industrial section of the city. It is there that the protagonist meets the old woman.

As I previously mentioned, an active reader must take into account the perceiver, and I like to focus on modifiers such as adjectives and adverbs. Going through the previous sections there are a few examples, such as plush bars, dubious-looking ‘club’, menacing faces, broken blinds, dark bars, and noisy garages. Modifiers show the narrator’s perception. There’s no need to explain why the faces are ‘menacing’ or why he happened to notice the ‘broken’ blinds. But these words show the mind at work behind the eyes of the narrator.

The last thing I would like to address is how narrators indicate mental processes. On the final page the narrator says, “I remember the floor and walls were covered in tiles, just that. That and the doctor’s redolent, reverberating surname, which I shall never forget.” Mental processes include memory, introspection, reasoning, and beliefs. Everyone assembles the world, remembering some things and forgetting others. But these activities create a unique world. My final thought is a question I can’t answer. Does this fictional Bilbao accurately represent the real Bilbao (whether current or historical)? Mimesis, the act of imitation, is a central aspect to critical theory. As an American who has never traveled to Bilbao, I can’t begin to debate the accuracy of Cillero’s writing. But this story is beginning to paint a picture of the Basque Country in my mind.

Gernika, the Basque spelling of Guernica, might be the most internationally recognizable part of contemporary Basque history because of Pablo Picasso’s painting, inspired by the German Luftwaffe’s “Condor Legion” bombing raid of the market town, killing anywhere from 126 to 1,654. The current population of the city is a little over 16,000. It was never a center of industry, but it did house the regional Basque Government and was therefore was a significant target for Franco.

“Black as Coal” presents this event from a much different angle. The story is about a young Basque boy who has an affair with a German pilot named Hans Schwarz. It is told in retrospect with the speaker setting the stage in the opening paragraph by stating that he lost his virginity the day after the bombing of Gernika. Here Montoia ties together the protagonist’s personal life with the Basque history. What makes it so interesting is the story’s perversity: a Basque boy sleeping with a German pilot. World War II films are often filled with French and Dutch women having love affairs with Nazis, women who after the war were shunned from society. Yet this is a story of a secret affair and feels confessional.

The beginning of the story sets up the narrator’s sexual frustration. “At first I thought I was the only sick one (144),” the narrator tells the reader. The sickness he’s alluding to is homosexuality, which he refuses to clearly state right away. On the third page of the story the reader begins to see the world through the protagonists eyes, “My eyes weren’t drawn to these girls he [Teo] admired so much, but to the stocky young workers who grabbed them boldly around the waist (145).” In the next paragraph the narrator tells the reader, “Death was my only way out.” Here the author creates tension between the protagonist and the world. Therefore when the German pilot seduces the boy, we, the readers, are torn in two. The audience knows that this pilot will be a part of the bombing raid but one some level the reader is empathetic to the protagonist’s situation.

In a comedic moment the narrator again shows the reader what he sees in the Germans: “I liked the Germans [….] They said please whenever they asked for anything and, once they had it, never failed to say thank you. They were so different from the arrogant Falangists or the Italians who spent all day perfuming themselves and preening their mustaches.” First we realize that the narrator is fighting against the Communists and with the Spanish and Italian Fascists. I won’t even begin to get into the complexities of what was at stake, but on a simple level Spain was split between Communist/Socialist against Madrid’s Catholic/military/centralist forces. It wasn’t simply Basque against Spanish. There were Catholic Basques who fought against the God-hating Communists. [For a heady read that really lays out the complexity of the war please read Hugh Thomas’ Spanish Civil War, a book I’m just starting.] But the portrayal of the Italians is stereotypical and humorous. And for a moment there is a weightlessness of young love in the story.

The reader follows the hidden love affair and how the narrator’s best friend, Teo, notices the marked change in protagonist’s mood. The story’s climax comes in a moment of marked optimism. The narrator gushes about how he loves his job and how he’s fantasizing about his lover. Then he sees a plane with a trail of smoke, but instead of running away from the Heinkel 51, he runs toward it. He’s convinced that Hans is in that plane. A policeman keeps him from running into the arcade where the narrator would’ve died. The city was under attack with an “inferno of the explosion: the whine of munitions, broken glass from the shop windows, shrapnel, ashes, and smoke [….] the policeman’s face was bloody and I could feel blood on my own cheeks as well. I panicked then, worried about the pilot (155).” I won’t go through the whole climax of the story. Some things are better read, to be enjoyed by experiencing them the way that they were meant to be. Tales should be read.

What I love about this story is how Montoia layered the text so that I would feel sympathy for this boy whose first love affair was tied in with his town being destroyed. There are so many different ways the story could be told. The narrator could’ve been a little girl instead of a boy. But there would be less tension resulting from the secret love affair. The pilot could’ve been a foot soldier from Italy (or Spain) but that wouldn’t have provided such a dramatic ending, one so intricately tied in with the historical event surrounding Gernika.

At this point in time I will say nothing about Bernardo Atxaga, except that he is the single most popular Basque writer in the world; for now, let’s focus on one of his tales. In my opinion this story couldn’t be a more perfect starting place, because it exemplifies how one’s inner-life, the world of self-perception and imagination, influences how one lives in the world.

Atxaga dramatizes the relationship between Teresa’s mind and the world in which she lives by shifting the point of view (POV), allowing the reader to observe the protagonist from multiple angles. Think of POV like a camera lens, except where film is limited to physical world, the written word has the ability to slip into the mind of a character, revealing thoughts and feelings.

This utilization of POV happens for the first time in the opening section, the focus moves from the physical world into the world of perception. Here the author presents how the protagonist sees herself. “Teresa had something wrong with her right knee, which meant that she had a slight limp, a fact that had been the cause of great sorrow to her ever since she was an adolescent” (31); this is the story’s first sentence, and it clearly ties Teresa’s body to her mind. The following sentence notes that this defect “was nothing very noticeable” (31). These passages have both the protagonist’s and the narrator’s POV; the narrator’s insight comments on Teresa’s self-perception and informs the reader on how it is influencing her life. Self-perception seems to have an antagonistic role in this story; it is the thing which is keeping her from being happy.

This is a big idea in fiction. There has to be something in the way of a character being happy. This obstacle has to be overcome in order for the protagonist to go through some sort of change. This tension in POV tips off the reader to that thing that’s getting in the way—in this case it’s the protagonist’s mind. The narrator goes on to explain that on her fourteenth birthday an Italian tourist who stayed at her parents’ boardinghouse exclaimed, “Teresa, poverina mia!” which translates to “my poor little thing.” Now the abstract thing, her self-perception, is tied into a phrase, a tangible memory that will haunt her. For me, this is good writing. Humans always tie emotions to memories, phrases, or events. We all have nicknames we want to forget but can’t.

Teresa has an emotional breakdown, which she lies to her family about, and spends most of the night journaling about her lameness from an objective point of view (32). Journal writing is one of those devices writers utilize to reveal a character’s inner workings to the reader. What the reader finds in this section is adolescent melodrama: “the true extent of her misfortune”, “there was no hope”, and “love, of course, would be denied her.”

The story jumps ahead fifteen years, making Teresa twenty-nine, and the first thing the narrator does is directly point out the melodramatic confession, which gives the reader key insight to the protagonist’s growth; there is also more trust forming between the narrator and the reader, who wants a reliable and intelligent narrator to guide them through the story. While the confession has been “almost forgotten” the words “continued to live in some fold in her brain, and sometimes, like a nagging refrain” (33). In this passage Atxaga makes a case for how influential one’s emotional life can be, whether or not the person is even aware of it.

The story begins to pull away from the inner workings of Teresa’s mind and out into the world, but even there Atxaga uses characters to bring the subtext to the surface. “‘Aren’t you forgetting that true beauty comes from within?’” her brother asks. Then the narrator states, “Even the word ‘brother’ was no longer what it once was” (34), which does two things at once, it both reveals the protagonist’s relationship with her sibling and how denotation impacts a word’s meaning within the protagonist’s mind. Good writing does at least two things at once. Here Atxaga works on the theme and character development.

After a number of pages that focus on Teresa’s family life, there is an echo of poverina mia, a repetition hints at the protagonist’s emotional world. At this point in the story the reader moves from 1979 to 1993 within two pages of text. In that section the reader watches as Teresa’s family dies and her diary entries return, but they have become less melodramatic.

Repetition with variation is a subtle thing writers do to create and develop themes in a text. For example, this phrase poverina mia is repeated but never in the same way. It carries the emotional gravity of the beginning of the story but treated slightly differently throughout the story. These echoes, which are intentionally created, allow for insight into the character’s psychology. Here is one example of where an author’s controlling hand creates narrative structure and meaning in a text.

When you go back to re-read this story look at how Atxaga uses both the narrator and Teresa to tell the story. Watch how he switches from third person narration to first confessions, how he moves closer to the protagonist and then further away—like a camera pulling in close and then pulling out to show a long shot. Keep in mind that this short story covers a lot of time in the protagonist’s life. It’s a great story for novice writers to look at with regards to manipulation of time and using different voices to move a story (both narrator and character).