The wound of the children from Ortuella

The classroom door slammed so hard we all jumped in our chairs and looked at our third grade teacher searching for answers, but she looked as shocked as the rest of us. We would later learn about the shock-wave effect. Before we could recover from the scare, the loud noise of sirens started filling the air as a stream of ambulances sped up towards Ganguren, one of Ortuella’s better-known neighborhoods. A girl in my class started crying, fearing that something went wrong with her stepmom, who was pregnant and due anytime.

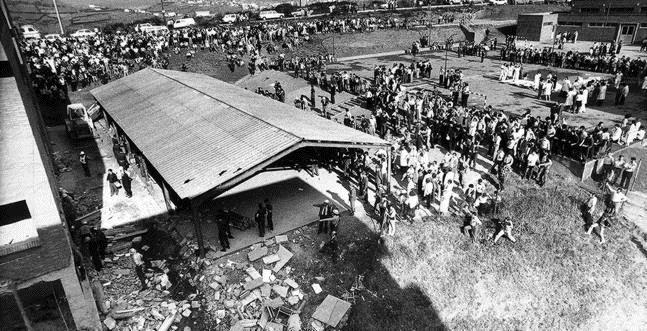

That’s how I remember the beginning of the saddest tragedy ever to strike my town, a small mining place in Bizkaia on the left bank of the Nervion River. On October 23, 1980, the lower part of Marcelino Ugalde National School blew up leaving 50 children and 3 adults dead. The boiler room exploded a few minutes before noon, when the city worker responsible for fixing the pipes lit a match, unaware of the gas leak.

I went to a different school, but I knew some of the kids that died in the explosion because they lived in my apartment building. I’m glad I was so young I couldn’t grasp just how painful, devastating and heartbreaking it must had been for the families.

Last month, on the 33rd anniversary of the catastrophe, the El Correo newspaper published an article remembering the event and reflecting on the causes that led to the explosion. I would have liked to share the news on the blog right away, but I found it extremely difficult to do the translation. It is always harder for me to go from Spanish to English, but in this case, it went beyond semantics.

I was seven years old when it happened. I am forty now with two kids of my own. They are not that much older than the five and six year-olds who died in the blast. I tried not to because it hurt too much, but I couldn’t help but putting myself in the place of those parents who lost their children. I remember the stench of the fire, the gas and smoke that lingered in Ortuella for days after the accident. I thought about those parents running frantically to the school, only to find chaos, body parts, and death scattered all over the site. I could only translate a few lines at a time before I felt like crying and had to stop until the following day.

The wound of the children from Ortuella

10.23.13 – 00:00 – TERESA COBO

The 27 funeral cars featured glass windows that allowed the interior to be seen. From my bedroom window, I saw them pass by in their slow procession along Santander road, with the rest of my neighbors along the Left Bank of the river who came out at that time to their balconies and windowsills. Each of the first 24 vehicles carried two little white coffins side by side. The last 3 cars each carried a large dark casket, undoubtedly the ones holding the bodies of both teachers and the lunch lady who died in the explosion at Ortuella’s school. We had already seen on TV the day before some of the boys and girls now resting inside the 48 ivory boxes. Dead students with their hair and clothes covered in dust being carried by shaken adults. There were parents holding their own children after finding them lifeless amidst the chaos.

The tragedy that sent Bizkaia into collective distress the day before marched underneath our windows the following day. There was a strange silence in the streets. There was not traffic on the N-634 highway. The road to Santander was closed to facilitate the transit of the funeral procession. The day before one lane had been enabled for emergency vehicles use only, when there were still children to be saved. The 48 children extracted from the rubble on Thursday would be buried on Friday.

On October 23rd, 1980 at noon, when the almost 900 students at Marcelino Ugalde National School in Ortuella had returned to class after recess, an explosion that could be heard up to three miles away caved in the floor of two classrooms on the first floor. Of the 120 children that were buried under the rubble, 48 were dead and the 34 that were rescued alive had to be taken to the hospitals in Cruces, Basurto, and San Juan de Dios. Twelve of the students were in critical condition. One of them, Alvaro, passed away on October 28. Francisco Javier died on November 4. He was the last victim, victim number 53. Most of the students who perished were five or six years old.

The gas leak and the match

The cause of the explosion was an accumulation of propane gas in the school’s basement due to a leak in the supply pipes. That day, the city plumber descended through a trap door to fix the drain in the kitchen sinks. The match he lit to warm up a section of pipe served as the trigger. Later, he was able to tell the story himself despite the serious burns he suffered in both arms. The result: 50 dead children and 3 dead adults, many families devastated, and a collective trauma.

It was around four in the afternoon when the transfer of the caskets shook up the locals in the Left Bank of the river, who saw the procession from their balconies and windows. The bodies taken to the morgue at the Cruces and Basurto hospitals had to be moved to the warehouses of Talleres Noguera in Ortuella, where the funeral chapel had been set up and over 10,000 people from all corners of Bizkaia were already waiting. Thousands of others were still trying to get to Ortuella by car, bus or on foot.

The commotion was general. As it always happens in the face of disasters and massacres with dozens of human casualties, a wave of solidarity swept through Bizkaia. The newspaper articles prove it. An avalanche of people arrived to the site of the explosion as soon as the news spread. That surge of good will ended up obstructing the evacuation efforts and hindered the onsite help to those slightly wounded by cuts from the shattered glass resulting from the shock wave. Traffic towards Ortuella was held up for six hours. Hundreds of people who didn’t know what to do to help went to donate blood to the hospitals spontaneously, almost one thousand the hospital in Cruces, despite there being enough reserves and without an official request.

The causes for collective deaths do not increase or reduce the pain of those who suffer them; they only alter the level of their rage or channel their fury in a particular direction. In Ortuella, there were no terrorists to blame or a psychopath to curse. Initially, there was talk of a terrorist attack, as that year there was a continuous trickle of policemen, civil guards, soldiers and even civilians killed by ETA. That possibility was soon discarded. It was an accident. But nothing is ever completely random. It was not by chance that it happened in a working neighborhood. It was way more likely that a public school from a mining area in the left bank of the Nervion blew up than a private school from the rich areas of the right bank of the river. Sometimes there is no guilty party, but there are almost always perpetrators.

Warnings from parents

The Delegation of Education in Bizkaia had requested a 700-million peseta subsidy (around $57,000) from the Department of Education to switch to diesel oil the school facilities operated by propane gas before the start of the school year. The parents’ associations had repeatedly demanded replacing the type of fuel used for heating and in the kitchens since they considered it essential to the safety of their children. The Department itself acknowledged that it had received “several warnings related to the risks caused by gas leaks and explosion in a boiler room” and made the families’ claim its own. The pipes, which lacked more expensive cathodic protection, had corroded and maintenance was neglected.

The Department only granted 10% of the budget requested by Bizkaia. Included in the list of schools where help was needed was the National School Marcelino Ugalde in Ortuella, which needed an investment of 2.4 millions of pesetas (around $20,000) to upgrade the facilities. Someone would later regret no having taken it seriously. At the cost of 53 lives, there was finally money available to eliminate the use of propane in the schools and reinforce the pipes.

Several schools in the Left Bank refused to resume classes before their facilities underwent a safety inspection. They had to close their doors because parents would not send their kids to school. The government carried out a general of safety inspection of conditions in public schools, especially in those that, like the one in Ortuella, were built under the Urgency Plan for Bizkaia, in areas with a rapid population growth.

90% of the population in Ortuella was made up of working-class families that immigrated in the 1950s drawn by the industrial and mining activity, as then Mayor Manuel Fernandez Ramos explained to EL CORREO. The 5 and 6-year old students that died in Marcelino Ugalde were the sons and daughters of lathe operators, mechanics, peons, the unemployed… They were the children and grandchildren of people from Galicia, Leon, Extremadura… There were also Basques. One of them, Miguel, the only black child, was the son of a Guinean construction worker.

“All your life is a lie”

The lawsuit resulting from the explosion in Ortuella’s school was dismissed. The state, liable in its role as civil subsidiary, was responsible for awarding compensation. Some of the victims’ relatives lashed out against the plumber who went to fix the pipes with his blowtorch, but the court acquitted him. His daughter was also at the school, in the eighth grade, when the match her father lit set off the gas bubble accumulated in the basement. She was unharmed. The worker, of course, was unaware of the gas bubble.

With or without perpetrators, the Marcelino Ugalde tragedy was unbearable. One couple lost all three of their children. Other families lost two. One of the parents, who was unemployed, gave the following explanation the day he buried his son Andres, who was going to turn six that week: “It’s like you suddenly wake up and they tell you that your whole life is a lie, that it was a dream. That you did not have those children.” Each case was a tragedy, including the three adults. The dead teacher was the mother of a one-and-a-half-year-old girl.

The explosion in Ortuella left a profound mark in Bizkaia that has yet to disappear 33 years later because the victims were children, many children, young children. And dead children hurt in a radical way.

Special thanks to Mark Bieter and Chad Transtrum, who helped remove the “accent” from my translation. Both Mark and Chad run their own blogs, both filled with interesting stories, some fictional, some reflections on their life experiences. Check them out at bieterblog.com and the open road.

A great article (and translation), and very interesting to get your perspective on such a horrible event. I can’t even imagine what those parents went through, and of course what that plumber must have felt for the rest of his life. It’s never fun to remember things like this, but it’s a good reminder to never take anything for granted.

Thanks, Mark. The translation is better in part thanks to you. And like I say in the post, I’m glad I was so young I couldn’t completely grasp the meaning of what happened that day. Thanks for reading and stopping by to leave a comment.