“To learn to read is to light a fire; every syllable that is spelled out is a spark”

Victor Hugo (Les Misérables, 1862)

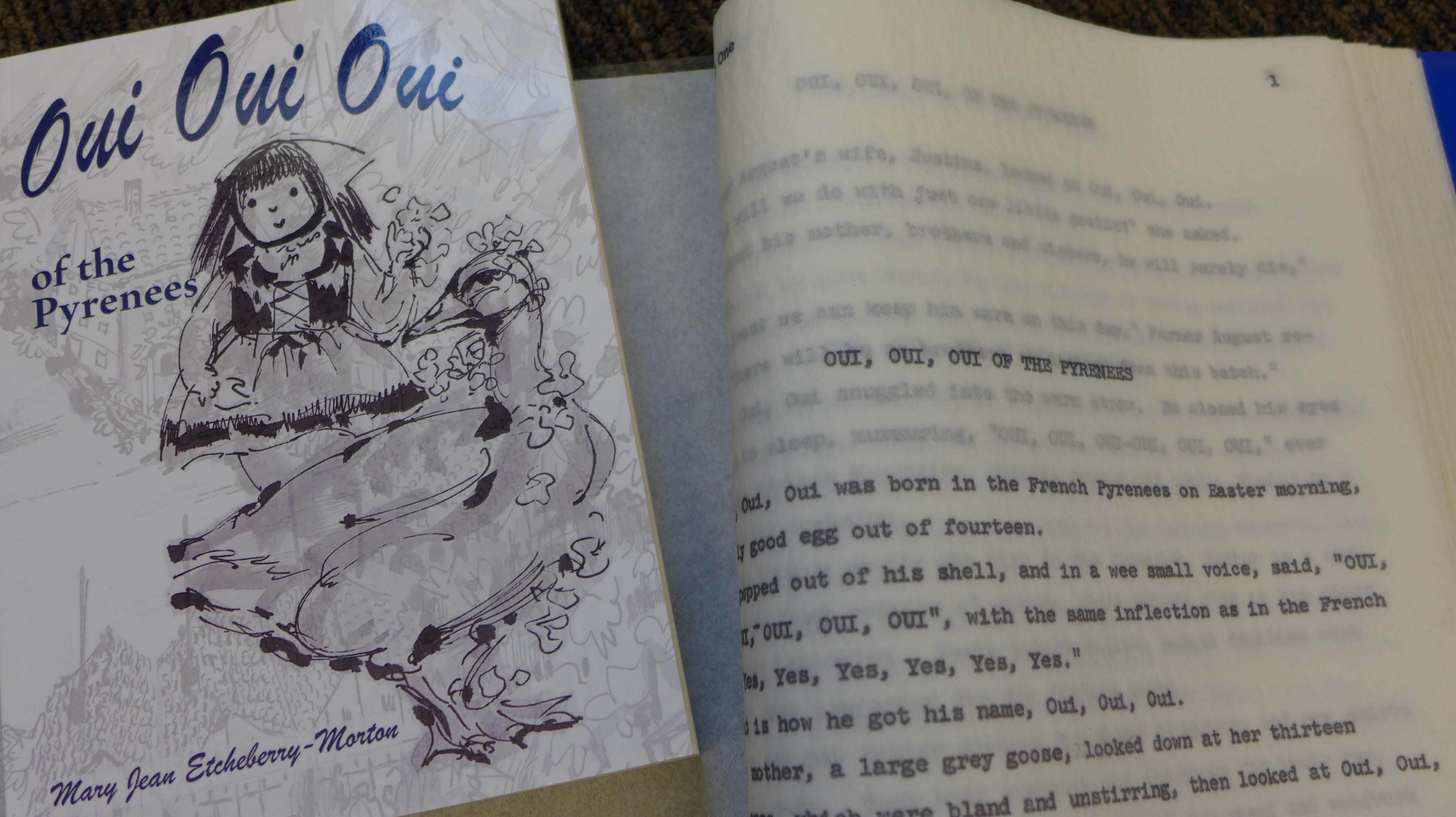

Against the backdrop of the secular Basque immigration history to the United States of America, a five-year-old girl, Maite Echeto, awaits the return of her father to the Old Country with her mother. In a visit to her cousins’ farm Maite meets a new-born goslin, by the name of “Oui Oui Oui,” that she ends up adopting. As one could imagine this is the beginning of their numerous and unexpected adventures throughout the colorful countryside of the Basque Country in France (Iparralde). Maite and the goslin are the main characters of the children’s book Oui Oui Oui of the Pyrenees.

Oui Oui Oui of the Pyrenees is the posthumous and first short story of Mary Jean Etcheberry-Morton. As a well-known local artist she also illustrated the book with original drawings. Mary Jean was born in 1921 in Reno, Nevada, and passed away in 2008 in Verdi, Nevada. She lived in Iparralde for a number of years in the 1950s. According to her family, “Mary Jean had a vehicle and was popular with the family because the roads then were in bad shape. She lived most of the time in a little house named Bakea, in Laxia of Itxassou [Itsasu], Lapurdi.”

Mary Jean’s parents were Jean Pierre Etcheberry and María Simona “Louisa” Larralde. Jean Pierre was born in 1891 in the small town of Saint-Just-Ibarre (Donaixti-Ibarre), in the Basque province of Lower Navarre, Nafarroa Beherea. He arrived in New York City at the age of 18. He worked as a sheepherder in Flagstaff, Arizona, and later on in the Winnemucca area. Jean Pierre arrived in Reno around 1914 and worked for the Jeroux family, a successful rancher at that time. María Simona “Louisa” was born in 1896 in Erratzu in the province of Nafarroa. She was the seventh of ten children, of whom six migrated to Nevada and California. Louisa arrived in New York City in 1914. Upon arrival in Reno, she worked as a maid in the mansion of the Jeroux family. “No doubt this is where she met her future husband Jean Pierre Etcheberry,” Paul Etxeberri, a nephew of Mary Jean, states. They married in 1917 in Reno and had three children: St. John, Paul John and Mary Jean. A decade later, Jean Pierre and Louisa bought a sheep ranch in southwest Reno and managed the Santa Fe Hotel, a successful Basque boardinghouse in downtown Reno, for over thirty years. Jean Pierre passed away in 1943, and Louisa in 1989 at the age of 93.

Mary Jean has now become part of Basque-America’s literary legacy, alongside Frank Bergon (Jesse’s Ghost), Martin Etchart (The Good Oak, The Last Shepherd), Robert Laxalt (Sweet Promised Land, The Basque Hotel…), Gregory Martin (Mountain City), and Monique Urza (The Deep Blue Memory), among others.

Before passing away Mary Jean entrusted her great-nieces, Marylou and Jennifer Etcheberry, with her precious manuscript, although it was just recently published.

Book cover of Oui Oui Oui of the Pyrenees alongside the original type-written manuscript. Photo by Pedro J. Oiarzabal, July 2013, Reno Nevada.

Book cover of Oui Oui Oui of the Pyrenees alongside the original type-written manuscript. Photo by Pedro J. Oiarzabal, July 2013, Reno Nevada.

Oui Oui Oui of the Pyrenees was published by the Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno in 2012, the second book of its Juvenile Literature collection. It follows Mark Kurlansky’s The Girl Who Swam to Euskadi, published in 2005 in English and Basque. With more than eighty titles ranging from diaspora and migration books to graphic novels it is by far the largest publishing house in the world on Basque topics for the English-speaking audience. Not shy to admit that academic presses should welcome other types of non-academic quality literary works, the Center for Basque Studies has issued a call for the first annual Basque Literary Writing Contest. (Please note: Entries closed on September 15, 2013.)

Marylou Etcheberry, proud great-niece of Mary Jean Etcheberry-Morton, poses with a copy of Oui Oui Oui. Photo by Pedro J. Oiarzabal, July 2013, Elko, Nevada.

Marylou Etcheberry, proud great-niece of Mary Jean Etcheberry-Morton, poses with a copy of Oui Oui Oui. Photo by Pedro J. Oiarzabal, July 2013, Elko, Nevada.

Oui Oui Oui of the Pyrenees is a welcoming breath of fresh air for the English-speaking reader, and especially for its younger members, regardless of their ethnic and cultural background. I hope that many more titles would follow the adventures of Maite and her goslin.

“My dearest darlings,” Jacque, Maite’s father, writes. “This is the letter I’ve dreamed of writing for four long years…Our future in America looks bright, and I can look forward to having my darlings with me…” This might well echo the wishes of many families that became strangled due to the physical separation upon leaving their homes and their loved ones behind. It very much resembles the family histories of our recent past. For Maite and her mother, it marks the beginning of a new quest.

Many thanks to Paul Etxeberri for gathering information on the Etcheberry family.

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno)

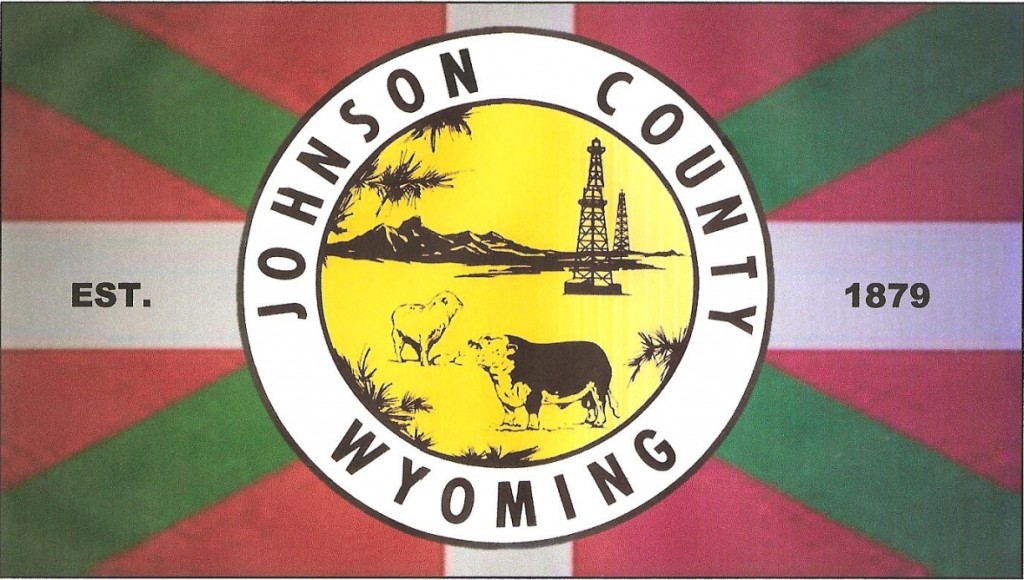

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno) The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag

The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag