“[La luna] es una piedra que se hunde en un lago de memoria, un espejo opaco, una sonrisa sin dientes”

(Iosu Expósito en Beñat Arginzoniz, Pasión y muerte, 2013: 48)

En la pista de despegue.

La velocidad se incrementa. La fuerza me empuja contra el respaldo del asiento… ¿Y si todo terminase aquí? ¿A dónde irían mis últimos pensamientos? ¿Y si todo terminase en este instante? Me apresuro a buscar un bolígrafo y un trozo de papel en el bolsillo del abrigo que reposa sobre mis piernas. Escribo con premura estas líneas que leen. Ya estamos en el aire. El instante ya ha dejado de existir.

Amanece en Bilbao. Febrero de 2015.

Amanece en Bilbao. Febrero de 2015.

En el aire.

Miro a mi derecha. Ha amanecido. Entre nubes grises, rayos de luz roja. Dejo atrás ese ya Bilbao post-apocalíptico de Gabriel Aresti, “Oskarria zabaltzen da / euskaldunen lurrean” (“Rompe un rojo amanecer / en la tierra de los vascos”).

Me sumerjo en la lectura del último libro de Joseba Zulaika sobre una generación que ya tenía mayoría de edad cuando mis ojos vislumbraron por primera vez el mundo. “Ese Minotauro ciego se convertiría no solo en la expresión de la batalla amorosa librada por Picasso, sino también en el emblema de nuestra generación, la generación de ETA” (Vieja luna de Bilbao. Crónica de mi generación, 2014: 24). Entre mis manos yace el testamento de una generación, que en sí alienta la limitación de nuestra condición imposible. Se convierte en el deseo inacabable de conseguir lo improbable.

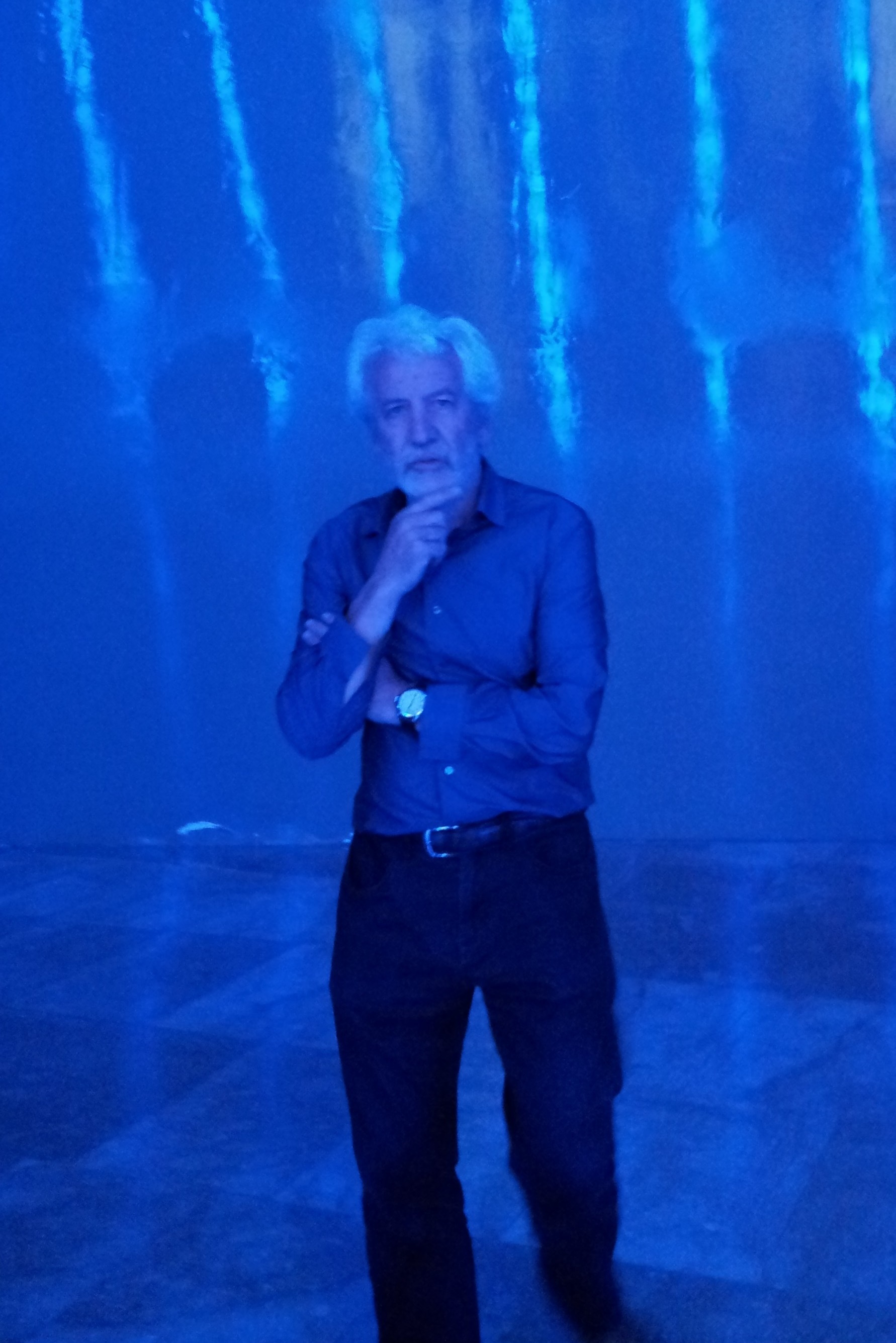

Zulaika en el Guggenheim Museoa. Mayo de 2015.

Zulaika en el Guggenheim Museoa. Mayo de 2015.

En Pasión y muerte de Iosu Expósito, Beñat Arginzoniz narra los últimos días del guitarrista de Eskorbuto. Es un Iosu enfermo que no se resigna a morir. “Ahora es la luna la que te busca. La luna te busca por las esquinas de la sorpresa. Sientes en tu espalda su mano helada, sus blancos dedos de cera, y escuchas su voz de ecos dormidos y de metales tristes” (2013: 48).

En Zulaika Bilbao también se resiste a morir. Parafraseando al fallecido Philip Levine, originario de la ciudad de Detroit, ésta al igual que el Bilbao dantesco de Zulaika o de Aresti es una ciudad devastada, la más devastada quizás, en la que “no hay menor atisbo de grandeza heroica. Lo único que queda son hombres, animales, plantas y flores que insisten en afirmar su derecho a la existencia” (The Art of Poetry No. 39, 1988). Cual ave fénix de la postmodernidad, “incluso después de las ruinas y la derrota persistió el mandato: debes cambiar tu vida, debes transformar la ciudad”, Zulaika proclama. Bilbao resucita.

Guggenheim Museoa. Abril de 2015.

Guggenheim Museoa. Abril de 2015.

De similar manera que el avión batalla entre nubes, y el horizonte se discierne, no dejo de preguntarme por la fantasía aceptada de esa línea imaginaria que separa el cielo y la tierra, delimitando la frontera entre el reino de los dioses y el de los humanos. Ponemos rumbo a Budapest. Hoy atraparemos el infinito. El avión ha virado y el sol me ciega.

Llegamos a Budapest. El bolígrafo ha explotado en mis manos. Las marcas de la tinta han crucificado mi mano derecha. Ha dejado más huellas que los renglones aquí escritos. ¿A dónde irán estas palabras? ¿A quién le importarán?

En Budapest.

Tránsito por sus calles. Unas calles que poco tenían que ver con Rapsodia de sangre, una película de 1957 de Antonio Isasi-Isasmendi que recreaba la Hungría del otoño de 1956 bajo el horror del régimen soviético. La película había sido parcialmente filmada en Bilbao, convirtiendo al Nervión en el improvisado, aunque algo famélico, substituto del todopoderoso Danubio de la “Guerra Fría”. Sucumbíamos a un verdadero juego de artificio. Sucumbimos al exceso. En una de nuestras idas y venidas por la ciudad, la antropóloga Mariann Váczi conversa sobre Zulaika, su trabajo y por su puesto sobre su último libro. “¿Ves la luna?”, me pregunta. Era una esfera plena de luz que se proyectaba como nunca sobre los edificios de Buda. La ultima luna llena del año. Era aquella vieja luna de Bilbao que nos perseguía en Budapest y se bañaba en las mansas aguas del Nervión-Danubio.

Hablamos sobre un futuro prometedor y sobre su primer libro como si de un recién nacido se tratase (Soccer, culture and society in Spain. An ethnography of Basque fandom, 2015). “Más de cinco años de trabajo y en dos meses lo tendré en mis manos. ¿Qué se siente cuando por fin lo puedes tocar con tus propias manos?”. “Tan pronto lo tengas delante de ti ya no te pertenecerá, nos pertenecerá a todos”, le conteste.

Mariann Váczi. Diciembre de 2015.

Mariann Váczi. Diciembre de 2015.

En Bilbao.

Aterrizamos. Llueve. “La pasión de lo real”. El hecho mismo de la vida parece que se debate en el derby del Athletic y la Real. Mientras el equipo “local” alineaba a más jugadores guipuzcoanos que el “visitante”, éste contaba entre sus filas con más jugadores de Bizkaia que los de la cantera de Lezama. Ambos equipos yacían a los pies de la verdad. Se retrataban ante la efimeridad de la identidad; ante el espejo inverso de la supervivencia.

Hacia Reno.

Retorno. Regreso a las últimas páginas de Vieja luna de Bilbao. El círculo se está completando. La lectura está a punto de terminarse y el capítulo de mi nueva estancia a punto de iniciarse. Desde la lejanía, Bilbao es nuestro Sergio al que ya no puedo volver. “No finaliza el viaje. No. Yo nazco, nací, yo nazco en la palabra. Ella es el carmín rojo de los deseos” (Delicatessen Underground. Bilbao Ametsak, 2008).

[Nota: Todas las fotografías son de Pedro J. Oiarzabal ©]

Celebración del tradicional

Celebración del tradicional

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno)

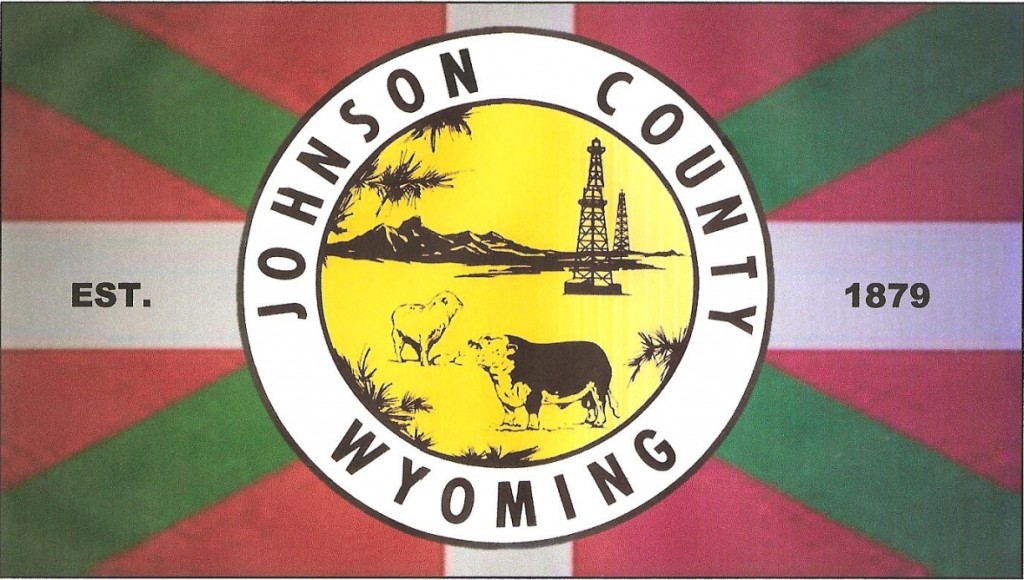

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno) The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag

The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag