Pete Cenarrusa, 2009. Argazkia: Glenn Oakley©.

Pete Cenarrusa, 2009. Argazkia: Glenn Oakley©.

Pete Cenarrusa duela astebete hil zen, 95 urte zituela. Arraroa da, hasteko, Pete ezerengandik “defendatzeaz” mintzatzea. Bere gurasoak inguruko euskal herrietan hazitako etorkinak izan ziren, baina milaka miliatara ezagutu ziren, Idaho erdian. Pete-en lehen hizkuntza euskara izan zen, eta bizitza osoan zehar jarraitu zuen euskaraz hitzegiten, batzuetan ingelesezko hitzak sartuz erdian.

Pete Idahoko Unibertsitatera joan zen, boxeo taldean aritu zen eta nekazaritza eta abeltzantza graduak gainditu zituen (92 urte zituela, ikastaro gogokoenak elikadura, kimika organikoa eta bakteriologia zituela idatzi zuen blogean, “mundu guztiari gomendatuko nizkioke ikastaro hauek unibertsitatean”. Marineetan sartu zen 1942an eta abiazio begirale bilakatu zen haiekin. 59 urtez egin zuen hegan, 15.000 hegaldi-ordu baino gehiagorekin, istripu bakarra ere izan gabe.

Errepublikar bezala hautatua izan zen Pete Idahoko Ordezkarien Etxean 1950ean, eta bederatzi legegintzaldi bete zituen, hirutan Bozeramaile bezala. 1967an, Idahoko estatu idazkaria hiltzean, gobernadoreak postua betetzeko izendatu zuen, eta han zerbitzatu zuen 2003ra arte. Ez zen ohiko moldeko politikaria izan. Bere lagun eta oinordekoak hiletan jaso bezala, Pete ez zen hizlari ona; baina politikari gehienek ez bezala, Pete-ek bazekien hori. Hala ere, gaitza da haren arrakasta ezbaian jartzea: Pete-ek ez zuen sekula hauteskunde bat galdu, eta 52 urtez egon zen administrazioan, Idahoko historiako hautetsi batek inoiz egin duen denbora luzeena.

ABC Espainiar egunkari nazionalak “hil-mezu” bat argitaratu zuen, Javier Rupérez Estatu Batuetako espainiar enbaxadore ohiak idatzita. Rupérezek Pete “euskal separatista” deitzen du, Espainiaren aurkako “itsukeriaz” betetakoa, “bere heriotze egunera arte”. Duela hamarkada bat baino gertatutako gertakari batetatik gordetako pozoiz idatzitako artikulua da, Pete hil eta egun gutxira idatzitakoa. Pete-ek ez du bere burua defendatzerik orain. Horregatik sentitzen dugu hori bere ordez egiteko betebeharra.

Testuingurua marraztearren, Rupérez, egilea, ETAk bahitu zuen 1979an. Hilabetez egon zen bahituta. Askatu ostean, 26 euskal preso askatu zituzten espetxetik, eta espainiar legebiltzarrak euskal presoen tortura kasuak aztertzeko batzorde berezi bat sortzea adostu zuen. Ezin dugu jakin zer bizi izan zuen Rupérezek, eta nahiago genuke hala gertatu izan ez balitz. Zalantzarik gabe norberaren mundu ikuskera formatzen du halako gertaera batek. Baina Pete-ek ez zuen zerikusirik izan gertaera lazgarri harekin, eta jakin badakigu hark gaitzetsi egingo zukeela. Eta hor sartzen du hanka Rupérezek, Pete-ekin eta euskaldunekin orokorrean.

Bere Karreraren amaiera aldera, Pete-ek Idahoko legegintzaldian Euskal Herrian eta Espainiako gertakari kritiko batzuei zuzendutako adierazpen baten sarrera iragarri zuen. Ofizialki “memorial” bezala ezagutu zenak AEBetako eta Espainiako liderrak bake prozesuari heltzeko dei egin zien . 2002an, Rupérezek memorialaren berri izan eta berehala Idahora hegaz egin eta Espainiar presidentea, Estatu Saila eta Etxe Zuria erne jarri zituen. Bat-batean, Mendebaldeko estatu txiki baten legegilearen adierazpena lehertu eta nazioarteko albiste bilakatu zen.

Memorialaren inguruko bozketa hurbiltzen zihoan heinean, tartean azaldu ziren alderdi ezberdinen arteko joan-etorriak ugaritzen joan ziren. Baina Pete-en erantzuna biribila izan zen – bera parafraseauz: noiztik hasi dira Amerikako Estatu Batuak kanpo-politika atzerriko gobernuen bidez egiten? Amaieran, Idahoko legebiltzarrak aho batez onartu zuen memoriala. Bertan, Idahoko euskaldunen historia eta Idahoko legebiltzarraren aurretiazko jarduerak deskribatu zien hala nola Frankoren diktaduraren errepresioa gaitzezpena, euskaldunek haien kultura mantentzeko ahalegina eta “bazterreko frakzio batzuk ezik” euskaldunen agertzen zuten bortxaren gaitzezpena jasoz.

Perfektua izan ala ez, demokratikoki hautatutako estatu legebiltzar autonomo batek aho-batez egindako adierazpena izan zen. Baina dirudienez atzetik ibili zaio Rupérezi urte guzti hauetan. Pete hil eta apenas 72 ordu igaro zirela, Rupérezek bortxaren aurrean begiak itxi dituen ahalegin baten “inspiratzaile eta buru ikusgarri” bezala salatu zuen Pete. Ahalegina, Idahoko senatuko buruak esan omen zuenaren arabera Espainiako aferei buruzko “tokiko ordezkarien muturreko ezjakintasunaren” eta “erretiratu aurretik hartutako azken ekimenarekin Cenarrusari atsegin emateko nahi orokorraren” ondorio izan zen, haren ustez. Rupérezen aburuz Pete ez zen Idahoko euskal komunitatearen adierazgarri tipikoa, eta baziren beste batzuk merezimendu handiagokoak.

Ez dugu Rupérez ezagutzen. Baina hark ere ez ditu euskaldunak ezagutzen, eta ziur dakigu ez zuela Pete ezagutu. Pertsona txikia behar du oso, hil berri denaren bizkarrean labana sartzen duenak. Gutako batzuk euskaldun amerikar hau pertsonalki ezagutzeko ohorea izan genuen. Edozelan ere, euskal nortasuna Euskal Herrian eta Euskal Herritik kanpo babesteko Pete-ek egindako ekarpen izugarria islatu nahi izan dugu (ikus hausnarketa pertsonalak About the Basque Country eta The Bieter Blog helbideetan). Mezu hau sinatzen duten lau blogek ezinezkoa dute geldi egotea Pete Cenarrusaren izenaren belzte publiko honen aurrean. Post hau libreki zabaldu eta zure egitera gonbidatzen zaitugu, zure blog, webgune edo sare sozialetan.

Rupérezek Mark Twaini hartu omen dion aipu batekin ixten du bere artikulua “Heriotza guztiak ez dira berdin hartzen”. Again egia da. Edonola ere, Rupérez jaunari ziurtatzeko moduan gaude Pete-en heriotza bizitzan zehar gauza handiak egin dituenak merezi dituen tristezia eta errespetu osoz hartua izan dela. Javier Rupérez bezalako pertsonentzat bereziki egokia den Mark Twainen beste aipu batekin amaitu nahi genuke: “Hobe da ahoa itxi eta ergela iruditzea, ahoa zabaldu eta zalantza oro uxatzea baino”.

Agur eta ohore, Pete

Sinatuta:

A Basque in Boise (ingelesez)

About the Basque Country (gastelaniaz)

Basque Identity 2.0 (euskaraz)

The Bieter Blog (ingelesez)

The Angry Brazilian (portuguesez)

8 Probintziak (frantsesez)

EuskoSare (ingelesez)

Buber’s Basque Page (ingelesez)

———————————————————–

PETE CENARRUSA (1917-2013)

Idahoko abeltzaina, euskal separatista.

96 urterekin zendua, Cenarrusak, hala laburtu baitzuen aitaren Zenarruzabeitia abizena, Idahoko estatuaren bizitza politiko eta sozialaren protagonismoa izan zuen ia hiru hamarkadatan zehar, behin baino gehiagotan hautatua izan zen tokiko legegintzaldian eta urteetan zehar bete zuen Estatu idazkari papera laborarien lurraldean. Haren gurasoek XX. mende hasieran egin zuten alde Euskal Herritik Estatu Batuetara, aberrikide askok legez, Amerikar Mendebaldeko abeltzaintzaren artzain eskaerari erantzunez.

Laster, euskal jatorriaz jakitun, lurraldekideen oroitzapen indibidual eta kolektiboak suspertzen saiatu zen eta hirurogeita hamargarren hamarkadan jarduera honek joera nazionalista indartsuak hartu zituen. Ez zuen alferrik nabarmendu EAJ-k “euskaldun unibertsalaren” “Sabino Arana” sariarekin.

2002an joera abertzale hauek ETAren jarduera terroristari ezikusia egiten zioten, Espainia eta Frantziaren “gatazkaren amaiera” negoziatzearen aldeko jarrera eskatzen zuen eta Euskal Herriaren autodeterminazioa eskatzen zuen Idahoko ganbera legegileen memorandumaren saiakeraren forma hartu zuten. Cenarrusa saiakeraren inspiratzaile eta buru ikusgarria izan zen, zeinentzako Ibarrecheren Eusko Jaurlaritzaren eta “Gara” eta “Egunkaria” kazetarietan gorpuztutako Batasunaren terminalen laguntza izan zuen. Lurraldean bisitari ohikoak hauek, orduko tokiko legegile eta oraingo Idahoko hiriburu Boiseko alkate David Bieterren abegikotasuna izan zuten.

José María Aznarren gobernuak George W. Bushen Etxe Zuria maniobraz ohartarazi zuen, eta honek Idahoko legegileei Espainia bezalako herrialde lagun eta aliatu batentzat iraingarri izan litezkeen testuak onartzearen desegokitasuna ikusarazi zien. Estatu Saileko bozeramaileak adierazpen irmoa egin zuen, tartean “Espainiar herriak erregularki ETA deituriko erakunde terroristaren biolentzia” jasaten zuela baieztatuz. Justuki Cenarrusa/Bieter/Ibarreche/Gara/Egunkaria memorialak jaso nahi izan ez zuena. Izan ere, babesle hauen ahaleginak ahalegin, testu zuzendua izan zen azkenean Idahoko legebiltzarkideek onartu zutena.

2003ko urtarrilean izan zuen Idahoko Senatuko presidenteak espainiar Gobernuari gertatutakoaren inguruko atsekabea adierazteko aukera, tokiko ordezkariek espainiar aferei buruz zuten ezezagutza sakonari eta Cenarrusari honek Estatu Idazkari izateari utzi aurretik atsegin eman nahiari egotzi ziolarik gertakari osoa. Robert I. Geddes senatariak euskal jatorriko abeltzain eta politikariari erregutu zion “hurrengoan Espainiari gerra deklaratu nahi izanez gero, aurretiaz ohartarazteko, gaizkiulerturik eman ez zedin”. Orduantxe bertan izendatu zuen Idahoko Senatuak Espainiak Washingtonen zuen enbaxadorea Estatuko ohorezko hiritar. Eta Espainiak ofizialki izendatu zuen Adelia Garro Simplot, euskal ondorengoa hau ere, demarkazioko ohorezko kontsul. Garro Garroguerricoechevarriaren laburdura da. Cenarrussak, zeinek ez dion hil arte Espainia konstituzional eta demokratikoaren aurkako itsukeriari utzi, ezin zen izan euskal komunitatearen ordezkari bakarra Idahon. Mark Twainek liokeen bezala, heriotza guztiak ez baitira berdin hartzen.

Javier Rupérez. Espainiako enbaxadorea Ameriketako Estatu Batuetan (2000-2004)

[* Itzultzailearen oharra: Izen eta abizen guztiak jatorrizko testuan bezala jaso dira, aldaketarik gabe.]

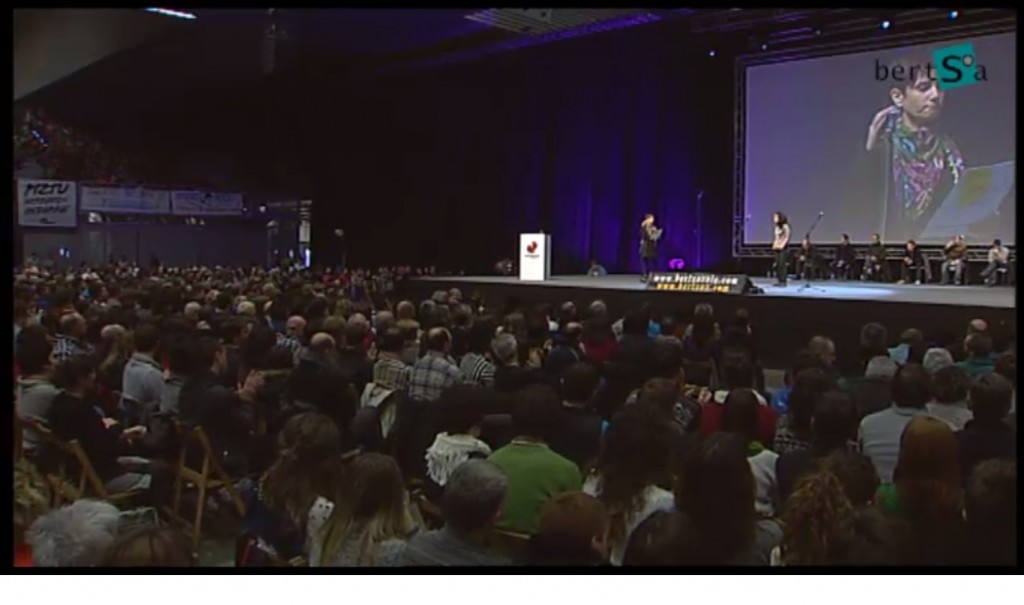

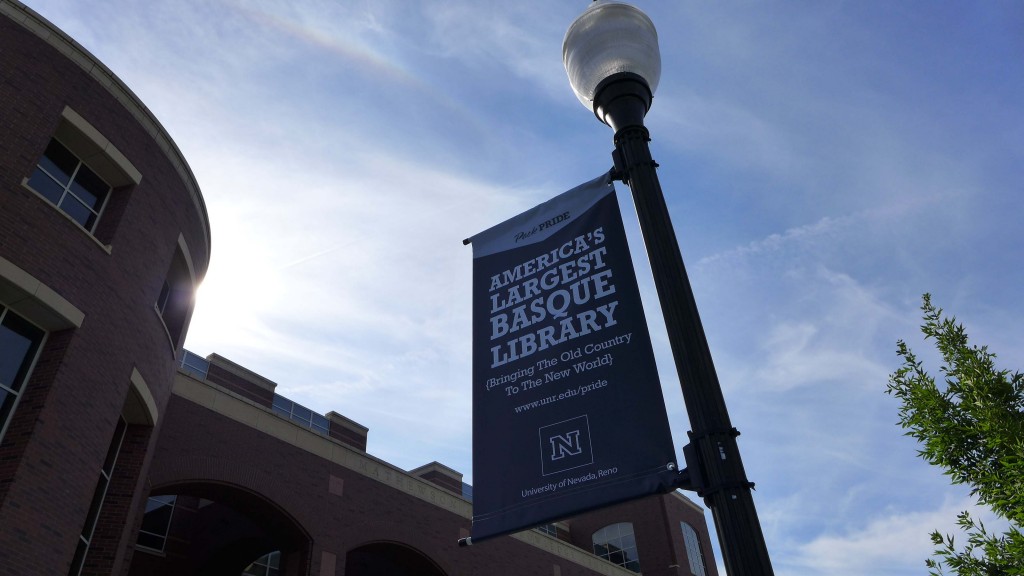

Homeland visitors coming to Boise should, if I may, prepare themselves to embrace the many different expressions of Basque identity and culture that will encounter, which may depart from pre-conceived ideas of what Basque culture and identity are as produced at home. Paraphrasing the friendly summer reminder for tourists, posted through many towns across the region, “You are neither in Spain nor in France. You are in the Basque Country,” please remember “Basque America is not the Basque Country” or is it? What do you think?

Homeland visitors coming to Boise should, if I may, prepare themselves to embrace the many different expressions of Basque identity and culture that will encounter, which may depart from pre-conceived ideas of what Basque culture and identity are as produced at home. Paraphrasing the friendly summer reminder for tourists, posted through many towns across the region, “You are neither in Spain nor in France. You are in the Basque Country,” please remember “Basque America is not the Basque Country” or is it? What do you think?

Pete Cenarrusa, 2009. Argazkia: Glenn Oakley©.

Pete Cenarrusa, 2009. Argazkia: Glenn Oakley©.