“I woke up as the sun was reddening; and that was the one distinct time in my life, the strangest moment of all, when I didn’t know who I was—I was far away from home…”

Jack Kerouac (“On the Road”, Part 1, Chapter 3, 1957)

One summer evening at dusk (Las Vegas, Nevada).

Upon arriving in Reno, Nevada, the memories I thought were gone for good came back quickly…the silhouettes of the mountains, the city lights, the fragrant smell of the sagebrush, and the name of the streets revealed themselves like invisible ink on a white canvas. Time did not temper the sentiments, and past stories did not diminish in size. It is always good to come back, even if it is impossible to return to the point where I left off.

Ainara Puerta, my colleague, and I embarked on a month-and-a-half-long field trip to conduct oral history interviews with Basque emigrants across the American West as part of a larger project called BizkaiLab, which is the result of an agreement between the Provincial Council of Bizkaia and the University of Deusto. The Center for Basque Studies in Reno became our base camp.

The Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno.

The aim of the project was (and still is) to preserve the rich migrant past of the Basque people for future generations by gathering information from the people who actually migrated and from those who had returned. Their stories travel landscapes of near and distant memories, between then and now, between an old home and a new home, and are invaluable for understanding our past and our present as a common people dispersed throughout the world.

The Star Hotel, Basque boardinghouse established in 1910 in Elko, Nevada.

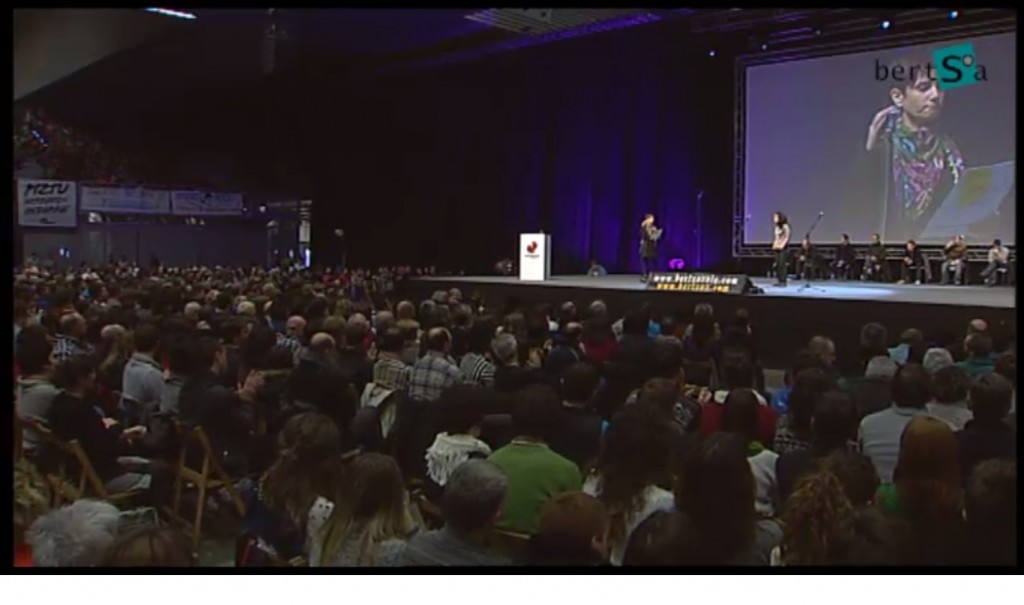

Understanding the relevance of preserving the life histories of the oldest members of the different Basque communities in America, the North American Basque Organizations, the Center for Basque Studies, the Basque Museum and Cultural Center, and the University of Deusto came together to organize, in a very short period of time, an oral history workshop to train community members in the interviewing process. This, we believe, is a way forward to empower the communities to regain ownership of their local histories as told by those who lived through the migration and resettlement processes.

The Oral History Workshop on Basque immigrants in the U.S. took place at the Basque Museum and Cultural Center (Boise, Idaho). Participants from left to right, Patty A. Miller, Teresa Yragui, Grace Mainvil, Gloria Lejardi, Gina Gridley, Goisalde Jausoro, David Lachiondo, and Izaskun Kortazar.

The North American Basque Organizations Board of Directors. From left to right: Marisa Espinal (Secretary), Valerie (Etcharren) Arrechea (President), Mary Gaztambide (Vice-president), and Grace Mainvil (Treasurer).

Similarly, the road led us to the Basque Cultural Center where we met the members of the Basque Educational Organization; great friends. Their constant work has turned into successful cultural projects in the San Francisco Bay Area, including the book, “Gardeners of Identity”, which I was honored to author.

The Board of Directors of the Basque Educational Organization at the Basque Cultural Center (South San Francisco, California). From left to right, standing: Ainara Puerta, Marisa Espinal, Aña Iriartborde, Yvonne Hauscarriague, Esther Bidaurreta, Nicole Sorhondo, and Pedro J. Oiarzabal. From left to right, kneeling down: Franxoa Bidaurreta, Mari-José Durquet (guest), and Philippe Acheritogaray. (Photograph courtesy of Philippe Acheritogaray)

By the time our trip was coming to an end we had driven over 4,000 miles (approximately 6.600 kilometers) through the states of California, Idaho, and Nevada in less than thirty days. We gathered over 21 hours of interviews with Basques from Boise, Elko, Henderson, Las Vegas, Reno, and Winnemucca. We conducted ethnographic work in the Basque festivals of Boise, Elko, Reno, and Gardnerville; took hundreds of photographs; attended community meetings; and met with several Basque associations and individuals.

On the road, Highway 50, “The Loneliest Road in America.”

Since the last time I was in the country many dear friends—some of whom had been key players in their Basque-American communities for decades—had sadly passed away. And yet, I found some comfort when witnessing a new generation of Basques, born in the United States, coming forward to maintain and promote our common heritage. This, in turn, will revitalize the Basque life and social fabric of their communities and institutions.

Oinkari Basque Dancers at the San Inazio Festival (Boise, Idaho).

Zazpiak Bat Reno Basque Club dancers preparing for the Basque festival in Elko, Nevada.

Throughout our road trip, we also perceived how some rural towns—once lively hubs filled with Basque social activities—now painfully languished, while others were certainly flourishing. It is a mixed sensation, a bitter-sweet feeling that comes to mind when I reflect back on the “health” of our Basque America. Are we writing the last chapters of the Basque culture book in the U.S.? I do not believe so or, at least, I do not want to believe it. I am not sure whether the answer to this question is based on evidence or just wishful thinking. Like many other things in life only time will tell.

The Winnemucca Hotel, one of the oldest Basque boardinghouses in the American West, established in 1863 (Winnemucca, Nevada).

The handball court in Elko, Nevada. A commemorative plaque for the mural reads as follows: “Ama, aita, euzkaldunak, inoiz ez dugu ahaztuko’…mother, father, Basques everywhere, we shall not forget! Our roots run deep.”

Thank you all for your love, hospitality and support. Special thanks to those who opened their homes and lives by sharing their memories, some filled with hardships and struggles as well as with hopes and dreams. Indeed, our Basque roots run deep in the American West, and we barely scratched the surface.

Eskerrik asko eta ikusi arte…

On a personal note, “Basque Identity 2.0” finally met “A Basque in Boise.”

With Henar Chico in the “City of Trees.” (Photograph courtesy of Henar Chico)

[Except where otherwise noted, all photographs by Pedro J. Oiarzabal]

Homeland visitors coming to Boise should, if I may, prepare themselves to embrace the many different expressions of Basque identity and culture that will encounter, which may depart from pre-conceived ideas of what Basque culture and identity are as produced at home. Paraphrasing the friendly summer reminder for tourists, posted through many towns across the region, “You are neither in Spain nor in France. You are in the Basque Country,” please remember “Basque America is not the Basque Country” or is it? What do you think?

Homeland visitors coming to Boise should, if I may, prepare themselves to embrace the many different expressions of Basque identity and culture that will encounter, which may depart from pre-conceived ideas of what Basque culture and identity are as produced at home. Paraphrasing the friendly summer reminder for tourists, posted through many towns across the region, “You are neither in Spain nor in France. You are in the Basque Country,” please remember “Basque America is not the Basque Country” or is it? What do you think?

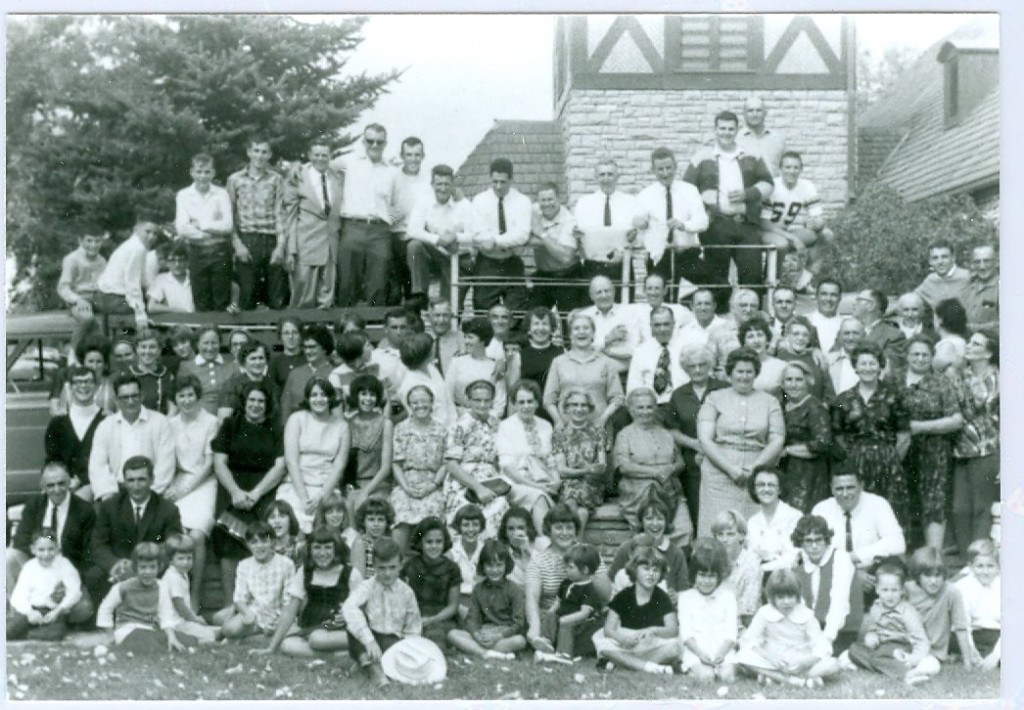

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno)

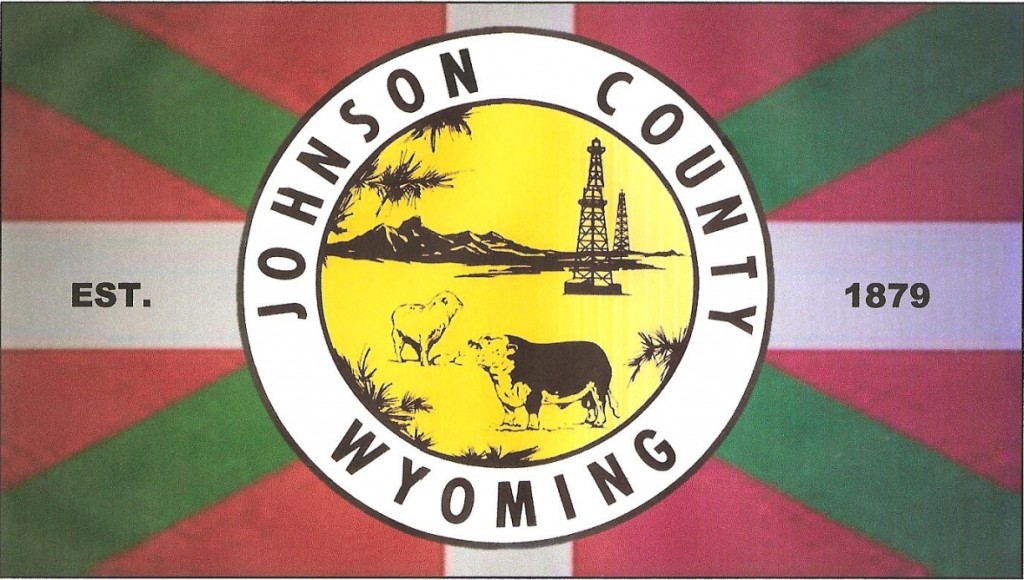

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno) The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag

The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag