In memory of Lydia (Sillonis Chacartegui) Jausoro (1920-2013)

“When he first came to the mountains his life was far away… He climbed cathedral mountains. Saw silver clouds below. Saw everything as far as you can see. And they say that he got crazy once. And he tried to touch the sun…”

John Denver (Rocky Mountain High, 1972)

By the time “Rocky Mountain High” became one of the most popular folk songs in America, the North American Basque Organizations (NABO) was an incipient reality. During a visit to Argentina, Basque-Puerto Rican bibliographer Jon Bilbao Azkarreta learnt about the Federation of Basque Argentinean Entities (FEVA in its Spanish acronym), which was established in 1955. Bilbao, through the Center for Basque Studies (the then Basque Studies Program) at the University of Nevada, Reno, was the promoter of a series of encounters among Basque associations and individuals, which led to the establishment of NABO in 1973. Its founding members were the clubs of Bakersfield and San Francisco (California); Ontario (Oregon); Boise (Idaho); Grand Junction (Colorado); and Elko, Ely, and Reno (Nevada).

Following last year’s field trip into the Basque-American memory landscape of migration and settlement throughout the American West, I arrived on time for the celebration of the 40th anniversary of NABO that took place in Elko, Nevada, during the first weekend of July. NABO’s 2013 convention was hosted by the Euzkaldunak Basque club, which coincidentally celebrated the 50th anniversary of its National Basque Festival.

North American Basque Organizations’ officers, delegates and guests. (Elko, Nevada. July 5th.) (For further information please read Argitxu Camus’ book on the history of NABO.)

North American Basque Organizations’ officers, delegates and guests. (Elko, Nevada. July 5th.) (For further information please read Argitxu Camus’ book on the history of NABO.)

On the last day of the festival, NABO president, Valerie Arrechea, presented NABO’s “Bizi Emankorra” or lifetime achievement award to Jim Ithurralde (Eureka, Nevada) and Bob Goicoechea (Elko) for their significant contribution to NABO. Both men were instrumental in the creation of an embryonic Basque federation back in 1973.

Bob Goicoechea (on the right), Valerie Arrechea, and Jim Ithurralde. (Elko, Nevada, July 7th.)

Bob Goicoechea (on the right), Valerie Arrechea, and Jim Ithurralde. (Elko, Nevada, July 7th.)

The main goal of my latest summer trip was to initiate a community-based project, called “Memoria Bizia” (The Living Memory), with the goals of collecting, preserving and disseminating the personal oral recollections and testimonies of those who left their country of birth as well as their descendants born in the United States and Canada. Indeed, we are witnessing how rapidly the last Basque migrant and exile generation is unfortunately vanishing. Consequently, I was thrilled to learn that NABO will lead the initiative. The collaboration and active involvement of the Basque communities in the project is paramount for its success. Can we afford to lose our past as told by the people who went through the actual process of migrating and resettlement? Please watch the following video so that you may get a better idea of what the NABO Memoria Bizia project may look like.

This video “Gure Bizitzen Pasarteak—Fragments of our lives” was recorded in 2012, and it shows a selection of interviews conducted with Basque refugees, exiles and emigrants that returned to the Basque Country. The video is part of a larger oral history research project at the University of Deusto.

While being at the Center for Basque Studies in Reno, the road took me to different Basque gatherings in Elko, San Francisco, and Boise.

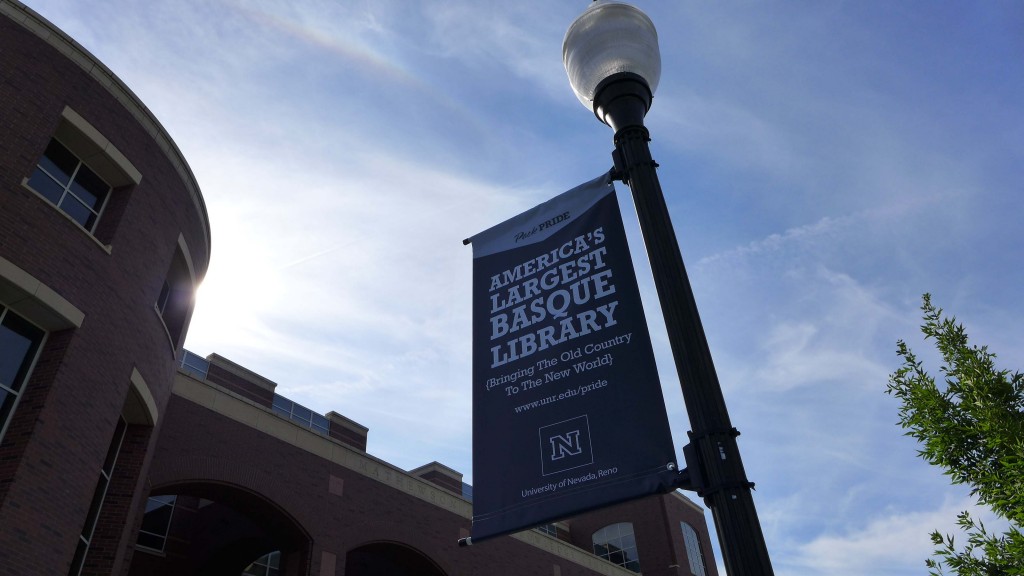

Basque Studies Library sign outside the Knowledge Center, University of Nevada, Reno. Established in the late 1960s, the Basque library is the largest repository of its kind outside Europe.

Basque Studies Library sign outside the Knowledge Center, University of Nevada, Reno. Established in the late 1960s, the Basque library is the largest repository of its kind outside Europe.

On the US-95 North going through Jordan Valley, Oregon.

On the US-95 North going through Jordan Valley, Oregon.

During my stay I was lucky to conduct a couple of interviews with two elder Basque-American women. One of them was Lydia Victoria Jausoro, “Amuma Lil,” who sadly passed away on November 14th at the age of 93. Lydia was born in 1920 in Mountain Home (Idaho) to Pablo Sillonis and Julia Chacartegui. Her dad was born in Ispaster in 1881 and her mother in the nearby town of Lekeitio in 1888. Both Pablo and Julia left the Basque province of Bizkaia in 1900 and 1905 respectively. They met in Boise, where they married. Soon after, Lydia’s parents moved to Mountain Home, where she grew up. She had five brothers. Lydia went to the Boise Business University and later on, in 1946, married Louie Jausoro Mallea in Nampa. Lydia and Louie had two daughters, Juliana and Robbie Lou. (Louie was born in 1919 in Silver City (Idaho) and died in 2005 in Boise. His father, Tomás, was from Eskoriatza (Gipuzkoa) and his mother, Tomasa, from Ereño, Bizkaia.) When I asked about her intentions for the summer, Lydia was really excited to share with me her plans of going to the different Basque festivals. She felt extremely optimist about the future of the Basques in America. Goian bego.

“Amuma Lil” at the San Inazio Festival. (Boise, Idaho. July 28th.)

“Amuma Lil” at the San Inazio Festival. (Boise, Idaho. July 28th.)

On July 19th I travelled to San Francisco, where I met my very good friends of the Basque Cultural Center and the Basque Educational Organization. On this occasion, I participated at their Basque Film Series Night, by presenting “Basque Hotel” (directed by Josu Venero, 2011). 2014 will mark the 10th anniversary of Basque movie night, one of the most popular initiatives in the Basque calendar of the San Francisco Bay Area.

With Basque Educational Organization directors Franxoa Bidaurreta, Esther Anchustegui Bidaurreta, and Marisa Espinal. (Basque Cultural Center, South San Francisco. July 19th. Photo courtesy of Philippe Acheritogaray.)

With Basque Educational Organization directors Franxoa Bidaurreta, Esther Anchustegui Bidaurreta, and Marisa Espinal. (Basque Cultural Center, South San Francisco. July 19th. Photo courtesy of Philippe Acheritogaray.)

This summer marked my first time in the United States, twelve years ago. I have been very fortunate to experience, at first hand, the different ways that Basques and Basque-Americans enjoy and celebrate their heritage. From an institutional level, the cultural, recreational and educational organizations (NABO and its member clubs) display a wide array of initiatives that enrich the American society at large, while private ventures flourish around Basque culture: art designs (Ahizpak), photography (Argazki Lana), genealogy (The Basque Branch), imports (Etcheverry Basque Imports, The Basque Market), music (Noka, Amuma Says No), books (Center for Basque Studies), news (EuskalKazeta)… A new Basque America is born.

Eskerrik asko bihotz bihotzez eta ikusi arte.

On a personal note, our Basque blogosphere keeps growing…

With Basque fellow bloggers “Hella Basque” (Anne Marie Chiramberro) and “A Basque in Boise” (Henar Chico). (Boise, Idaho. July 28th.)

With Basque fellow bloggers “Hella Basque” (Anne Marie Chiramberro) and “A Basque in Boise” (Henar Chico). (Boise, Idaho. July 28th.)

[Except where otherwise noted, all photographs by Pedro J. Oiarzabal]

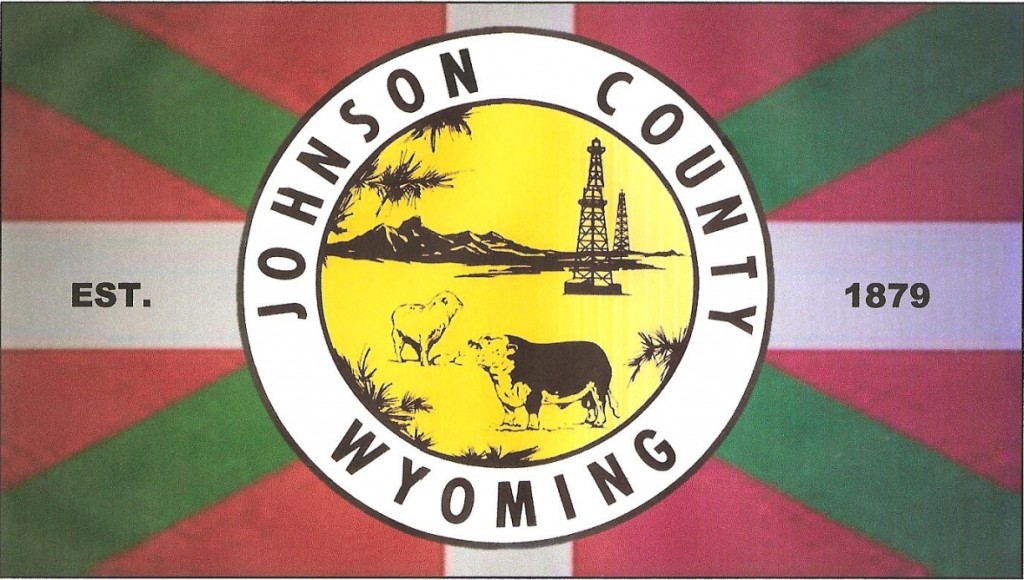

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno)

Basque group photograph at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, in Buffalo, Wyoming, in the late 1960s. (Photograph courtesy of the Center for Basque Studies Library, University of Nevada, Reno) The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag

The Johnson County, Wyoming “Basque” flag