Similar to the imminent art of improvising verses in the Basque language, or bertsolaritza, our life, especially in the digital world, is ephemeral. This oral tradition reaffirms and expresses an identity rooted in a specific area but with a global projection thanks to the emergent technologies of information and communication. Since its inception Basque Identity 2.0 has assumed the challenge of its own fugacity by exploring different expressions of Basque identity, understood in transnational terms, through a global medium. Perhaps, this comes down to accepting that our ephemeral condition is what really helps to shape our collective memory and identity, and which are constantly revisited and reconstructed.

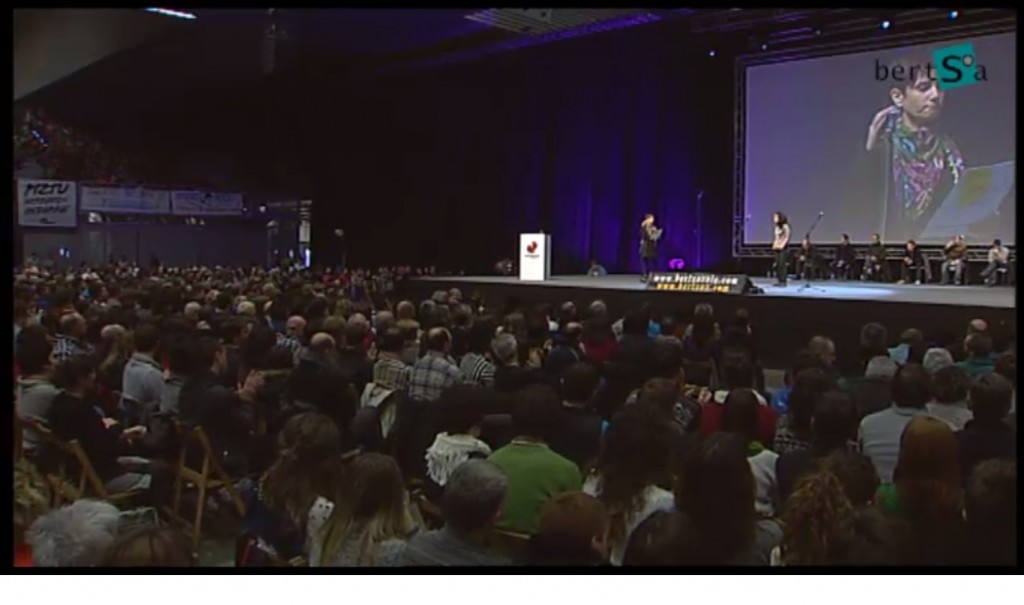

Maialen Lujanbio, bertsolari or Basque verse improviser, sings about the Basque diaspora. Basque Country Championship, Barakaldo (Bizkaia), December 15, 2013. Source: Bertsoa.

Maialen Lujanbio, bertsolari or Basque verse improviser, sings about the Basque diaspora. Basque Country Championship, Barakaldo (Bizkaia), December 15, 2013. Source: Bertsoa.

In June, we celebrated the 4th anniversary of Basque Identity 2.0. I would like to acknowledge our colleagues and friends from A Basque in Boise, About the Basque Country, EITB.com and Hella Basque for their continuous support and encouragement (“Sucede que a veces”—“It happens sometimes,” May post).

We began the year reflecting on our historical memory, which has increasingly become a recurrent topic in the blog for the past two years. Through the stories of Pedro Junkera Zarate—a Basque child refugee in Belgium from the Spanish Civil war—Jules Caillaux—his foster dad while in Belgium, and one of the “Righteous among the Nations”—and Facundo Sáez Izaguirre—a Basque militiaman who fought against Franco and flew into exile—I attempted to bring some light into a dark period of our history. Their life stories are similar to some extent to many others whose testimonies are critical to understand our most recent history of self-destruction and trauma (“Algunas personas buenas”—“Some good people,” February post). Some of these stories are part of an ongoing oral history project on Basque migration and return. As part of the research I was able go back to the United States to conduct further interviews and to initiate a new community-based project called “Memoria Bizia” (“#EuskalWest2013,” November post).

In addition, May 22 marked the 75th anniversary of the massive escape from Fort Alfonso XII, also known as Fort San Cristóbal, in Navarre, which became one of the largest and most tragic prison breaks, during wartime, in contemporary Europe. This was the most visited post in 2013 (“The fourth man of California,” March post).

On the politics of memory, I also explored the meaning of “not-forgetting” in relation to the different commemorations regarding the siege of Barcelona 299 years ago, the coup d’état against the government of Salvador Allende 40 years ago, and the 12th anniversary of the terrorist attacks against the United States. Coincidentally, September 11th was the date of these three historical tragic events (“El no-olvido”—“Not-to-forget,” September post).

The Spanish right-wing newspaper ABC led the destruction of the persona of the late Basque-American Pete Cenarrusa, former Secretary of the State of Idaho (United States), by publishing an unspeakable obituary. Nine blogs from both sides of the Atlantic (A Basque in Boise, About Basque Country, Basque Identity 2.0, Bieter Blog, 8 Probintziak, Nafar Herria, EuskoSare, Blog do Tsavkko – The Angry Brazilian, and Buber’s Basque Page) signed a common post, written in four different languages, to defend Cenarrusa (“Pete Cenarrusaren defentsan. In Memorian (1917-2013)”—“In defense of Pete Cenarrusa. In Memorian (1917-2013),” October post). It was a good example of digital networking and collaboration for a common cause. However, this was not an isolated event regarding the Basque diaspora. Sadly, nearly at the same time, ABC’s sister tabloid El Correo published a series of defamatory reports against the former president of the Basque Club of New York. Once again, ignorance and hatred laid beneath the personal attacks against public figures, for the only reason of being of Basque origin.

Basque literature, in the Spanish and English languages, was quite present in the blog throughout the year. Mikel Varas, Santi Pérez Isasi, and Iván Repila are among the most prolific and original Basque artists of Bilbao, conforming a true generation in the Basque literature landscape of the 21st century (“Nosotros, Bilbao”—“We, Bilbao,” April post). The year 2013 also marked the 10th anniversary of “Flammis Acribus Addictis,” one of most acclaimed poetry books of the late Sergio Oiarzabal, who left us three years ago (“Flammis Acribus Addictis,” June post). The blog also featured the late Basque-American author Mary Jean Etcheberry-Morton’s book, “Oui Oui Oui of the Pyrenees”, which is a welcoming breath of fresh air for the younger readers (“Yes!” July post).

This has been a year filled with opportunities and challenges. Personally, I have been inspired by the greatness of those who keep moving forward in spite of tragedy and unforeseen setbacks, and by those who are at the frontline of volunteering (“Aurrera”—“Forward,” December post).

Thank you all for being there. Now, you can also find us on Facebook. I would love to hear from you. Happy New Year!

Eskerrik asko eta Urte berri on!

(NOTE: Remember to use Google Translate. No more excuses about not fully understanding the language of the post).

(Photograph by Pedro J. Oiarzabal)

(Photograph by Pedro J. Oiarzabal)