a: to make a final choice or judgment about

b: to select as a course of action

c: to infer on the basis of evidence: conclude

d: to bring to a definitive end

e: to induce to come to a choice

f: to make a choice or judgment

Within the context of the swell and unparalleled power that we individuals are able to exercise in the so-called Western society regarding the ability to choose from an unborn baby’s sex to religion, citizenship and even physical aspect, it is incomprehensible how difficult it becomes when addressing the issue of exercising the rights of political national groups and their capability to decide on a collective basis.

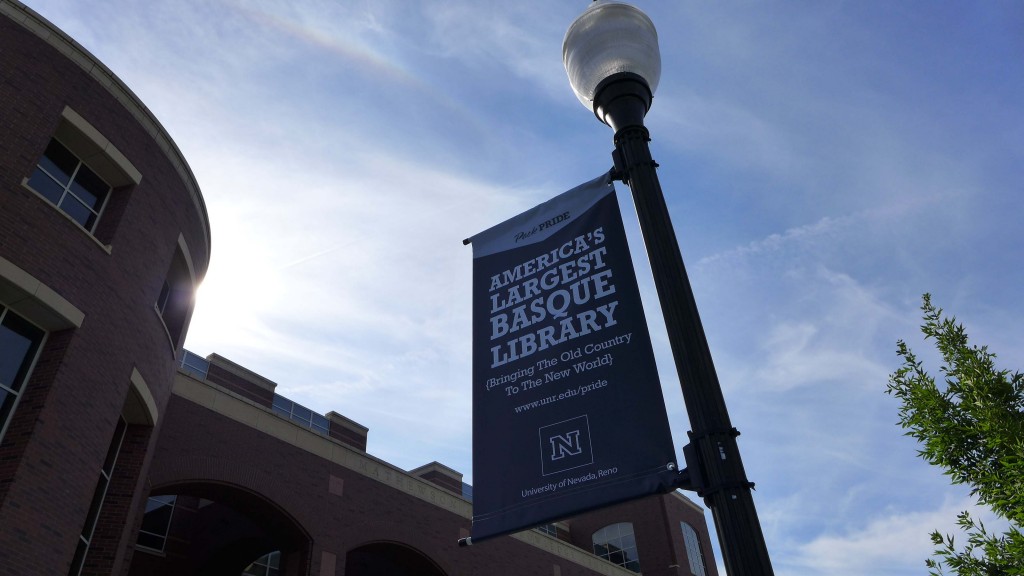

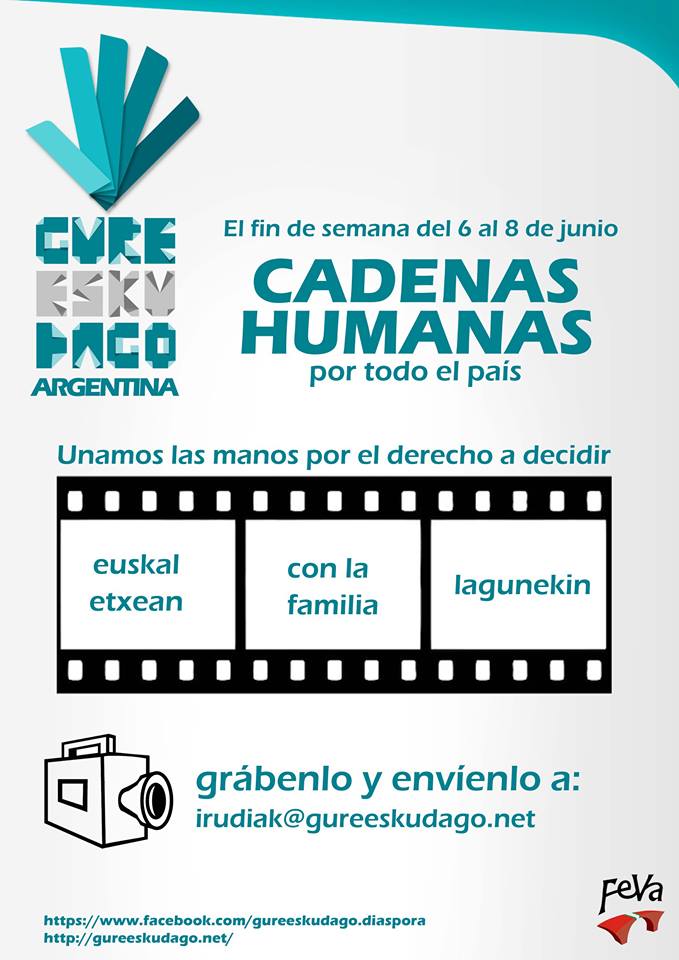

From the 28th to the 30th of May, international experts debated the meaning of Basque nationhood in a globalizing world in Bilbao. Organized by the International Catalan Institute for Peace, the Peace Research Institute of Oslo, and the University of the Basque Country, the meeting explored the meaning of sovereignty from many different angles as it is everyday practiced. On the last day of the conference, local social groups shared their experiences on practicing “sovereignty” by acting upon it on their daily decisions, for instance, about promoting the use of the Basque language, Euskera, the respect for our environment, and defending the workers’ rights. Among those groups, Gure Esku Dago (It’s in our hands) embodies this theoretical concept of “sovereignty” as an initiative in favor of the right to decide. On the 8th of June, this popular initiative will organize a human chain of 123 kilometers uniting the cities of Durango (Bizkaia) and Iruña (Navarre). As of today, more than 100,000 people are supporting the event, in the homeland as well as in the diaspora.

“Gure Esku Dago” in Argentina. Supported by the Federation of Basque-Argentinean Entities (FEVA).

“Gure Esku Dago” in Argentina. Supported by the Federation of Basque-Argentinean Entities (FEVA).

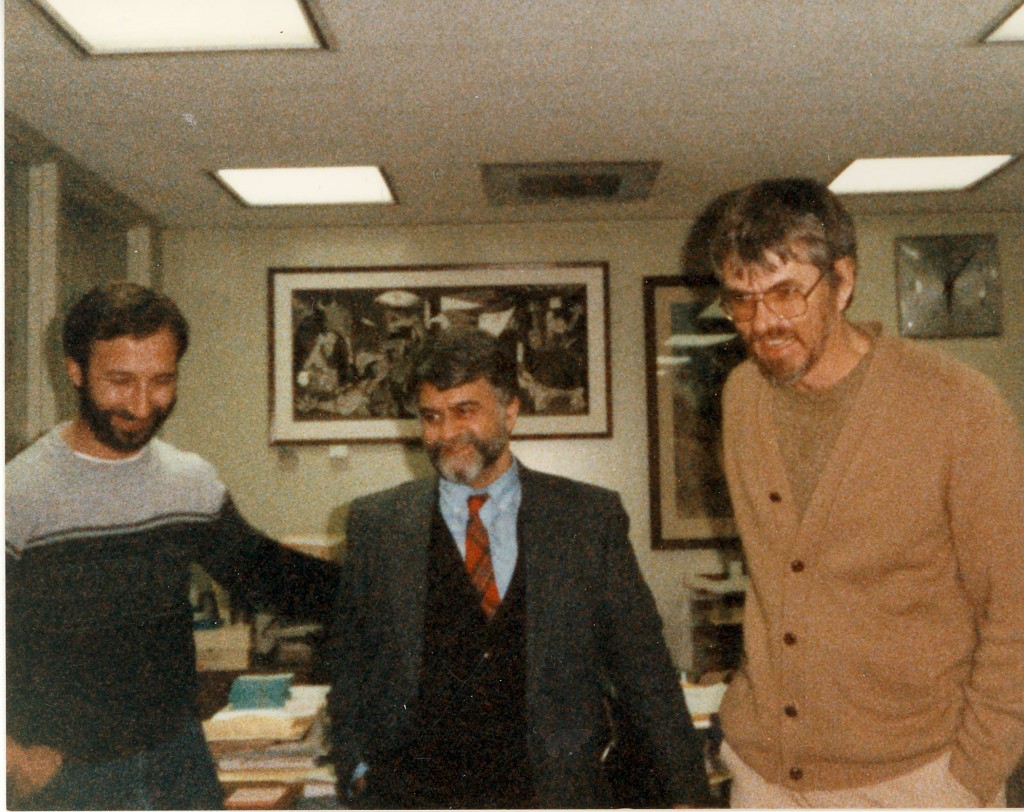

Coincidentally, on the 29th the Basque Autonomous Community Parliament (Basque Parliament, hereafter) adopted, by a majority vote, a resolution on the right of self-determination of the Basque People as a basic democratic right as it previously did in 1990, 2002 and 2006. Two days and 20 years earlier, the Public Law 8/1994, passed by the Basque Parliament, became the current legal framework of institutional relationship between the Basque Autonomous Community and the diaspora, which was established in order to “preserve and reinforce links between Basque Communities and Centers on the one hand, and the Basque Country on the other hand,” and to “facilitate the establishment of channels of communication between Basque residents outside the Basque Autonomous Community, and the public authorities of the latter.” Indeed, the passing of the law itself became a clear act of sovereignty, which legally recognized the existence of a large population of Basque people outside its administrative borders—a true transnational community of citizens—and provided a formal framework for collaboration. Looking back there is a need to acknowledge the visionary work done by Karmelo Sáinz de la Maza—the main person behind the law—or the late Jokin Intxausti—the first government delegate in charge of re-establishing contacts with the various Basque diaspora associations and communities—among many others.

Carmelo Urza, Jokin Intxausti, and William Douglass, at the then Basque Studies Program, University of Nevada, Reno (UNR), 1986. Photo Source: Basque Library, UNR.

Carmelo Urza, Jokin Intxausti, and William Douglass, at the then Basque Studies Program, University of Nevada, Reno (UNR), 1986. Photo Source: Basque Library, UNR.

Also, the anniversary of the Law 8/1994, which surprisingly has passed unnoticed, offers us an opportunity to rethink our identity in terms of a borderless citizenship within the context of the current Basque presence in the world. The fact is that the reality of today’s mobility and return to the Basque Country is quite different from past emigration waves. It is necessary, in my opinion, to adequate the law to the new flows of migration and return, while enhancing and strengthening the programs towards the needs and demands of individuals and associations with the goal of intertwining a solid global network based on common interests.