“A child associated with an armed force or armed group refers to any person below 18 years of age who is, or who has been, recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, spies or for sexual purposes. It does not only refer to a child who is taking, or has taken, a direct part in hostilities.”

(Paris Principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed groups, United Nations, 2007)

The Declaration of the Rights of the Child was adopted by United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1959. This international norm was followed, three decades later, by the Convention on the Rights of the Child (November 20, 1989)—the first legally binding instrument “to incorporate the full range of human rights—civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights”—and by the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (May 25, 2000). This protocol “establishes 18 as the minimum age for compulsory recruitment and requires States to do everything they can to prevent individuals under the age of 18 from taking a direct part in hostilities.” It entered into force on February 12, 2002, marking the International Day against the Use of Child Soldiers. Since then, more than 140 countries have ratified the protocol.

As of February 2012, 27 United Nation Member States have not signed or ratified the Optional Protocol, while another 22 have signed but not ratified it. According to the Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research 2011 has been the most violent year since World War II, with twenty more wars than in 2010. Currently, it is estimated that tens of thousands of boys and girls under the age of 18 take active part in armed conflicts in at least 15 countries. The children, once again, are powerless to escape from such violence. They are forced to fight or participate somehow “voluntarily” in popular insurrections that have taken place within the context of the Arab Spring, for instance. However, the military use of children is not a new phenomenon and goes hand by hand, almost inevitably, with our tragic history of human self-destruction. This was the case of some of the children caught at the outbreak of the war between Adolf Hitler’s Germany and Joseph Stalin’s Russia in June 1941. The children had previously been evacuated from Spain—immersed in a fratricide war—to Russia.

It is estimated that 30,000 Spanish children were evacuated during the Spanish Civil War, and 70,000 more left after the end of the war in 1939. Among them 25,000 Basque children went also into exile. Most of the children were temporarily sent to France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as well as Switzerland, Mexico, and Denmark. They became, and are still, known as “los niños de la guerra” (“the war children”) and the “Gernika Generation,” in the specific Basque case.

Between March 1937 and October 1938 nearly 3,000 children, between 5 and 12 years old, were evacuated from Spain to then the Soviet Union in four expeditions. Most of the children were from the Basque Country (between 1,500 and over 1,700), and Asturias and Cantabria (between 800 and 1,100). In the majority of the cases their parents were sympathetic to the anarchist, socialist, and communist ideals. On June 12, 1937 over 1,500 children and 75 tutors (teachers, doctors, and nurses) left the Port of Santurtzi in the Basque province of Bizkaia on board of the ship “Habana.”

From the moment of the children’s arrival to the German invasion of Russia they lived in good care in the so-called “Infant Homes for the Spanish Children.” There were 11 homes located in the current Russian Federation—including 1 in Moscow and 2 nearby Leningrad—and 5 in Ukraine—including 1 in Odessa and another in Kiev. Soon, their lives were, once more, dramatically turned upside-down. The homes had to be evacuated.

“The war children” from Spain and tutors, August 1940, Russia (Image source: Sasinka Astarloa Ruano)

“The war children” from Spain and tutors, August 1940, Russia (Image source: Sasinka Astarloa Ruano)

During the Siege of Leningrad, the children Celestino Fernández-Miranda Tuñón and Ramón Moreira, both from Asturias, were 16 and 17 years old respectively at the time of enlisting as volunteers to defend the city, while Carmen Marón Fernández, from Bizkaia, worked as a nurse and dug trenches at the age of 16. Over 40 children were killed before they could be evacuated in 1943. It is considered the longest and most destructive city blockade in history. It resulted in the deaths of 1.5 million people and in the evacuation of 1.4 million civilians.

The survivors of Leningrad together with the rest of the children were taken to remote areas such as today’s republics of Georgia and Uzbekistan, and Saratov Oblast in southern Russia. It is during this time when it is reported that some children were victims of sexual assaults and exploitation, and a few of them ended up in delinquent gangs in order to survive.

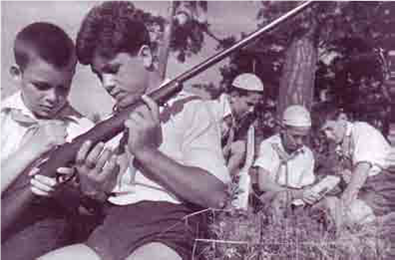

Paramilitary training in one of the children’s colony. Shooting practices were a norm in many of the homes (Image source: Spanish Citizenship Abroad Portal)

Paramilitary training in one of the children’s colony. Shooting practices were a norm in many of the homes (Image source: Spanish Citizenship Abroad Portal)

According to the Spanish Center of Moscow, over 100 “niños de la guerra” voluntarily enlisted in the Red Army, while many others had to carry out some type of work to support the war efforts alongside their schooling time. For instance, Begoña Lavilla and Antonio Herranz, both from Santurtzi, worked at an arms factory in Saratov at the age of 13 and 14, respectively. Eight of the Basque niños—six of them from the “Kiev home”—entered in combat after receiving flight training courses in a military academy. It has been said that some of the children were able to pass themselves off as older men such as Luis Lavín Lavín who was just 15 years old at the time. The eight young Basques were Ignacio Aguirregoicoa Benito (born in Soraluce in 1923), Ramón Cianca Ibarra, José Luis Larrañaga Muniategui (born in Eibar in 1923), the aforementioned Luis Lavín Lavín (born in Bilbao in 1925), Antonio Lecumberri Goikoetxea (born in 1924), Eugenio Prieto Arana (born in Eibar in 1922), Tomás Suárez, and Antonio Uribe Galdeano (born in Barakaldo in 1920). Larrañaga, Uribe, and Aguirregoicoa died in 1942 (Ukraine), 1943 (Dnieper), and 1944 (Estonia), respectively. Aguirregoicoa took his own life in order to avoid being captured by the enemy.

Between 207 and 215 Spaniards were killed as active combatants at the Eastern Front of World War II (also known as the Great Patriotic War; June 22, 1941-May 9, 1945), while another 211 people died of extreme starvation, disease, and the intensive bombardments. According to Lavín, 50 of the enlisted “children” out of a total of 130 were killed during the war.

After two long decades of exile, the first convoy of “children” was allowed to return to Francisco Franco’s Spain in 1957. As of 2012, it is estimated that 170 “niños de la guerra,” all of them over 80 years old, live in the former Soviet Union. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the bombings of Basque cities and villages and the evacuation of their children—fatidic preamble to World War II.

For more information see the interview (in Spanish) to Mateo Aguirre S.J., on the Democratic Republic of Congo child soldiers’ situation at Alboan’s EiTB Blog; and the Child Soldiers International organization; and Luis Lavín Lavín’s conference of 2007 (in Spanish).