“Someone said that forgetting is full of memory, but it is also true that the memory does not give up”

(Mario Benedetti, Echar las Cartas, 2002)

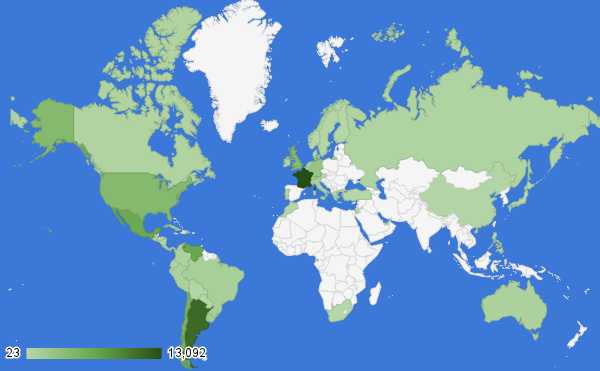

In 2013, the number of Basques abroad, registered with a Spanish consulate from a municipality in the Basque Autonomous Community (Euskadi), was nearly 72,000. As shown in the map, they are living in over 50 countries, being France (13,000), Argentina (11,000), Venezuela (6,500), Mexico (6,300) and Chile (5,000) the countries that host the majority of them. All evidence indicates that Basques will progressively go abroad. A recent survey points out that nearly half of the Basque young population are willing to look for a job in a foreign country. Sixteen percent of Basques between 15 and 29 years old believes that in the future they will be forced to “emigrate abroad to work, unwillingly.” For instance, from 2009 to 2013, the number of Basques registered with a Spanish consulate has increased by 35%. They preferred destination was the European Union, followed by Asia and America.

“Number of Basques residing abroad.” Source: Spanish National Statistics Institute, 2013.

“Number of Basques residing abroad.” Source: Spanish National Statistics Institute, 2013.

On December 18, 2013, the University of Deusto presented the results report of its first social survey on Euskadi (DeustoBarómetro Social / Deusto Gizarte Barometroa, DBSoc). According to the report, in relation to the attitudes toward the welfare policies, the five areas where the majority of Basques believed that there should not be budget cuts under any circumstances were “health” (86%), “education” (79%), “pensions” (68%), “unemployment benefits” (49%), and “Science and R+D” (36%). That is to say, while nearly three quarters of the Basque society’s priorities focused on health, education and pensions, the five areas that obtained the least support were “embassies and consulates” (7%), “defense” (6%), “equality policies” (6%), “development cooperation” (5%), and “support for Basques abroad” (5%).

After taking into account the internal degree of relevance established by comparing the response options, the result of the question related to the welfare policies in the Basque society seems logical, particularly, within the context of a prolonged and deep socio-economic and financial crisis and extreme public budget cuts. When reflecting on the possible reasons behind such low support, it comes to my mind the existing distance between the Basque society and its diaspora, the knowledge that homeland Basques might have on the diaspora, and above all their interest on the Basques abroad.

The respondents established a degree of significance regarding the option “support for Basques abroad” in relation to their own quotidian and vital world. It can be considered the “emotional distance” that exists between the respondents and the “Basques abroad”, which goes together with the existing geographical, temporal and/or generational distances. Secondly, evidences suggest that the degree of knowledge that homeland Basques (especially the youngest generations) might have on diaspora Basques and the degree of proximity to the diaspora issue is marginal. This knowledge has been relegated to the confines of the intimate memory of migrants’ family members and close friends and to the micro-history of villages and valleys. To a great extent, the history of Basque emigration, exile and return is not adequately socialized, for instance, through formal education (e.g., textbooks and didactical materials). Consequently, the collection, preservation and public dissemination of the testimonies of Basque migrants is not only necessary but urgent. This indicates that there is a wide “information and knowledge gap” between the Basque society and the Basques outside the homeland. But, beyond the inquiry regarding such a lack of awareness about the Basque diaspora, a fundamental question remains open. Is there a motivation or interest to know?

Finally, in addition to the aforementioned gaps, the absence of the issue of the Basque diaspora in the public debate in Euskadi impedes it for being even discussed or included in the Basque political parties’ list of priorities. This goes hand in hand with the fact that the diaspora lacks of a voice and of an organized lobby, preventing the penetration of any of its potential official discourses into the Basque society. In other words, nowadays, the Basque diaspora is defined by a high degree of invisibility and silencing in the daily life as well as in the imaginary of the Basque homeland rather than the opposite.

What all this tell us about the Basque identity and the homeland’s collective imaginary? Do you believe that the integration of the history of the Basques abroad and the returnees into the official homeland history and collective memory will have an effect on its visibility and recognition? Do you believe that emergent technologies of information and communication have a role to play in narrowing the gap between the Basque Country and its diaspora?

Please leave us your opinion or alternatively follow the conversation in Twitter, #BasquesAbroad, @deustoBarometro and @oiarzabal

I would like to thank Iratxe Aristegi and the rest of the team of DeustoBarómetro Social / Deusto Gizarte Barometroa at the University of Deusto for their help.

Here, for the Spanish version of this post “¿La comunidad invisible? #VascosExterior”

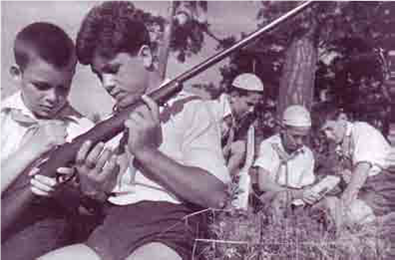

“The war children” from Spain and tutors, August 1940, Russia (Image source:

“The war children” from Spain and tutors, August 1940, Russia (Image source:  Paramilitary training in one of the children’s colony. Shooting practices were a norm in many of the homes (Image source:

Paramilitary training in one of the children’s colony. Shooting practices were a norm in many of the homes (Image source: