In the context of understanding the many processes that take part in the creation and development of the Basque identity (or Basque identities) this blog has attempted to understand and explain it from different perspectives. This has taken us to comprehend identity as a true glocal and multidimensional phenomenon. The Basque Country and its diaspora (or diasporas) are envisioned as a spatial and time continuum at the crossroads of tradition and modernity.

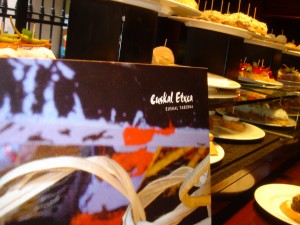

Like a puzzle, Basque Identity 2.0 has put together different stories to draw an image of past and present aspects of our culture and traditions, while arguing about the meaning of authenticity, the reproduction of our identity, and the preservation of our common homeland and diaspora history (“The Basque global time,” April post). In this regard, I explored the implication of Basque cuisine in Barcelona, Catalonia as an “appropriation” of the “Basqueness trademark” or “Euskadi made in” label (“Euskal Barcelona,” February post), the endurance of Basque traditional dance in San Francisco, California (“Zazpiak Bat,” June post), and the redefined symbol of Basque music as a representation of our identity globally (“i-bai musika,” December post).

Most of these stories echoed the voices of many Basques around the globe, which sometimes are intertwined with my own life story as reflected, for instance, in the January (“Extraño”—“Singular”), July (“Cartografía de emociones”—“Cartography of emotions”), September and October posts. In a sense, I described the diaspora as a psychological and emotional community, which is increasingly connected to the homeland as an attempt to break up all geographical and temporal barriers (“Connected,” March post).

During the past year, I have tried to bring attention to our exiles as exemplified by the breathtaking story of “La Travesía del Montserrat” (“The Crossing,” August post) as well as our returnees, whom somehow have become “the forgotten Basques” of our contemporary history. In “Entre culturas” (“Between cultures,” May post) I talked about the returnees’ positive role that may play as “cultural brokers” between the society at large and the new migrants in the Basque Country.

Finally, in the aftermath of the 10th anniversary of 9/11 (“¿Dónde estabas el 11 de Septiembre?”—“Where were you on September 11th?” September post), ETA declared the end of the violent episode in its history (“Trust,” October post), while the Basque government called upon the Basque institutional diaspora to promote a peaceful image abroad (“2003, 2011,” November post). This post became the most commented and visited in the history of the blog, which tells us about the significance of homeland politics in the Basque diaspora. However, the diaspora is far from being a homogeneous and united entity. It is as ideologically plural as the Basque society itself, whose collective and historical memory plays a crucial role for its survival.

Thank you all for being there. I would love to hear from you. Happy New Year!

Eskerrik asko eta Urte berri on!

(NOTE: Please feel free to use Google automatic translation service…and good luck with it).