“Many hundred dreams have been dreamed in our island but I do not know if they helped to brighten our existence. They grouped themselves around two objects—food and rescue”

(Carl Skottsberg at Paulet Island, 1903)

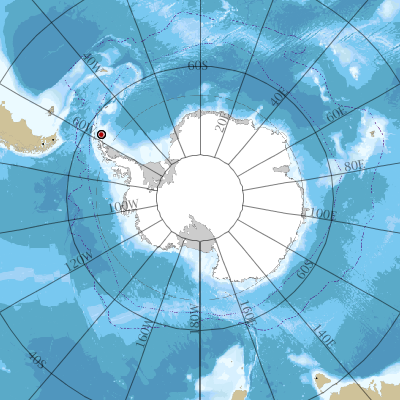

In the Antarctic Argentine Islands of the Wilhelm Archipelago lies a pretty tiny island called Irízar (65° 13′ 0″ S, 64° 12′ 0″ W). The Argentine Islands are a group of sixteen islands, which were named as such by Jean-Baptiste Charcot—scientific leader of the first French Expedition to Antarctica that took place between 1903 and 1905—in gratitude to the Republic of Argentina. One of the islands was named in honor of Basque-Argentinian Lieutenant Commander Julián Irízar who had previously led the rescue of the failed Swedish Antarctic Expedition in 1903.

The Antarctic Irízar Island (Map source: Australian Antarctic Data Center)

The Antarctic Irízar Island (Map source: Australian Antarctic Data Center)

It was the era of the international scientific and geographical exploration of Antarctica, which, in turn, also favored private commercial pursuits (e.g., the whaling industry) and fuelled the feeling of personal adventure by becoming, for example, the first person to reach the geographical South Pole. This era was initiated by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition, sponsored by the Belgian Geographical Society and led by navy officer Adrien de Gerlache in 1897, and it concluded in 1922 with the British Shackleton–Rowett Expedition. This was considered the last significant scientific voyage before the introduction of the aerial exploration in the late 1920s, which opened up a modern era for Antarctic discovery. It also meant the slow end of the maritime voyages of scientific exploration that began in the late 17th century.

During more than two decades sixteen major polar expeditions were launched by Belgium, the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, France, Japan, Norway, and Australia. It was some time before the revolution in transport and telecommunications technologies, and all pioneers’ efforts were confronted with the crude hostility of an unknown continent. Many crew members suffered severe injuries and others died under extreme weather conditions, lack of supplies, illnesses, and accidents.

The 1901 expedition led by Swedish scientist Otto Nordenskjöld and Norwegian explorer Carl Anton Larsen soon was about to face the hardships of Antarctica. As part of an agreement with the government of Argentina, military geologist José María Sobral Iturrioz joined the crew of Antartic, the expedition’s steamship. He became the first known Argentinian (and first Argentinian of Basque origin) to live in the southernmost continent of the planet. Nordenskjöld and five of his men were dropped off at Snow Hill Island in 1902 to establish a campsite from where to carry their work for one winter, while Captain Larsen sailed back to Malvinas. In November 1902 Larsen returned for Nordenskjöld and his group, but the ship was crushed by ice and finally sank 25 miles from Paulet Island. Both parties had to spend another isolated winter while ignoring each other’s fate. Their nightmare just began. A young sailor, Ole Christian Wennersgaard died in June 1903.

Concerned about the members of the expedition, Sweden, Argentina and France began to make arrangements for their rescue. Meanwhile, Carlsen’s party managed to reunite with Nordenskjöld’s group at Snow Hill where were successfully rescued by Lieutenant Commander Julián Irízar and its corvette Uruguay in November 1903. On December 2, 1903, the steam relief ship safely arrived at Buenos Aires after dealing with a huge storm that destroyed the mainmast and the foremast. It was greeted by tens of thousands of people. The rescue was considered one of the most triumphant and heroic episodes in the history of Antarctica as echoed by the international press of the day. It was also the first official voyage of Argentina to the frozen continent. Upon return Irízar was promoted to Captain.

The corvette Uruguay (Photo source: Fundación Histarmar)

The corvette Uruguay (Photo source: Fundación Histarmar)

Among the 22 members of the Uruguay, the surgeon, José Gorrochategui, was also of Basque ancestry. Irízar and Gorrochategui were the first known Basques or Argentinians of Basque origin who set foot on the Antarctic continent (in addition to Sobral). Sobral Iturrioz was born in Gualeguaychú and Gorrochategui in Concepción del Uruguay, both in the province of Entre Ríos. Irízar was born in Capilla del Señor, in the province of Buenos Aires, in 1869 and died in Buenos Aires in 1935. Gorrochategui’s parents were from the Basque province of Bizkaia—his father was from Bilbao and his mother from Bermeo. Irízar’s parents were also Basque migrants, but this time they were from the province of Gipuzkoa; his father, Juan José Irízar was from Oñati and his mother, Ana Bautista Echeverría from Zumarraga.

On December 10, 1903, the Basque association Laurak-Bat of Buenos Aires organized a banquet to honor Irízar and his crew for the rescue of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition as well as for Sobral Iturrioz. During the ceremony, Irízar and his officers were given a silver-plated copper medal, while the sailors might have received a copper medal. The Basque-language inscription in the silver medal read: “Guidontzi “Uruguay”-ko adintari Julian Irizar Jaunari. Biltoki “Laurak-Bat”-ek” (Obverse); “Joair Doaitea “Antartic”-ari laguntzeko * Buenos Aires 1903 *” (Reverse). (“The Center “Laurak-Bat” to Mr. Julian Irizar, captain of the ship “Uruguay” that leaves to help out the “Antarctic” * Buenos Aires 1903 *”).

The banquet at the Laurak-Bat clubhouse (Photo source: La Baskonia, Number 368: 1903).

The Laurak-Bat Irízar Medal (Images source: La Baskonia, Number 368: 1903). According to Glenn M. Stein, FRGS, polar and maritime historian, “this may very well be the only polar-related medal ever created in the Basque language.”

Irízar became Admiral of the Argentine Navy and retired after 50 years of military service. Through his career Irízar received many distinguished awards including the insignia of Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honor of France. On the 50th anniversary of the rescue, the Argentinian government built a monolith at the Buenos Aires port to commemorate “la hazaña de Irízar” (Irízar’s heroic deed). In 1979, the icebreaker of the Argentina Navy was named Almirante Irízar in his honor. The corvette Uruguay became a naval museum in 1967, and nowadays it is moored to the dock of Puerto Madero, Buenos Aires. The Argentine Antarctic summer base, built in 1965, was named after Lieutenant Sobral, considered the father of Argentinian explorations in Antarctica.

For more information (in Spanish) see: “1903 – Hazaña de la corbeta Uruguay y la colectividad baskongada” (Luis Héctor Carranza, 2003) and “Julian Irizar y la ‘Uruguay’” (Martha González Zaldua, 2003).

Many thanks to Shannon Sisco at the Basque Library, University of Nevada, Reno